Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 12-16-2018

Case Style:

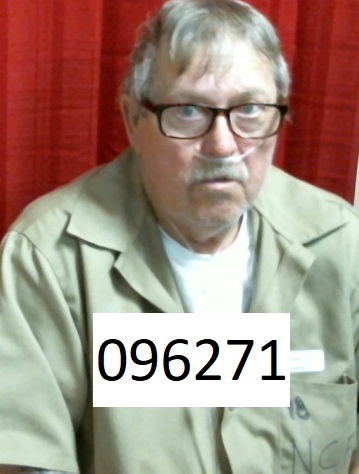

JESSE ALLEN STUMP V. COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

Case Number: 2017-SC-000557-MR

Judge: MEMORANDUM OPINION OF THE COURT

Court: Supreme Court of Kentucky

Plaintiff's Attorney: Andy Beshear

Attorney General of Kentucky

Thomas Allen Van De Rostyne

Assistant Attorney General

Defendant's Attorney: Clarence Hervey Hixson

Description:

Stump was indicted on July 11, 2012, of first-degree rape and incest1 for

the rape of his step-granddaughter, Sally,2 on April 14, 2012. After a two-day

1 Stump was also indicted of an additional count each of rape and incest relating to another victim. However, the charges for the other victim were severed from those relevant to this appeal.

2 In keeping with this Court’s practices, throughout this opinion, the minor victim’s name has been changed to protect her anonymity.

trial, beginning July 31, 2017, Stump was convicted of one count of first-

degree rape and sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment.

Sally indicated that she first reported the charged rape to her best friend.

The record reflects that she then reported the rape to a teacher at her school

on April 23, 2012. The teacher referred her to a school guidance counselor,

who called the Commonwealth’s abuse hotline. After speaking to the

counselor, Sally underwent a forensic interview on May 16. This interview was

conducted by Kimberly Cook at the Child Advocacy Center in Louisville,

Kentucky.

During this interview. Cook asked Sally if anything like the rape she

reported had happened before with Stump. Sally answered “[w]ith him? No.

Maybe. 1 think when 1 was little it happened before.” Cook proceeded

questioning Sally regarding possible rapes, to which Sally answered that she

was smaller and couldn’t remember what occurred and nothing else had

happened on any other day that she remembered. Following this interview,

Sally underwent a medical examination on June 8 at the Child Advocacy

Center.

Regarding the charged rape, Sally testified that Stump told her to go into

his bedroom, asked her to take off her shirt, pants, and underwear, and

instructed her to lie down on the bed. Sally said she complied with Stump’s

orders, and he touched on her sides and then put his penis inside her. Sally

further testified that she asked Stump to stop because it hurt. She said that

afterwards, he told her not to tell anyone about what he had done to her and

she went to be with her sister.

On October 27, 2016, (nine months prior to trial) the Commonwealth

filed a motion to introduce evidence pursuant to KRE 404(b). The motion

indicated that Stump had sexually assaulted Sally on numerous occasions

before April 2012. This motion was for an order to allow the Commonwealth to

introduce evidence—expected to be in the form of Sally’s testimony—of other

acts of sexual abuse Stump perpetrated upon Sally other than the isolated

incident set forth in the indictment. As attached in an appendix to Stump’s

brief to this Court, it appears the Commonwealth also emailed a copy of a

notice and motion pursuant to KRE 404(b) to Stump’s counsel on July 21,

2017. It was only after the Commonwealth sent this email to Stump’s counsel

providing a second notice (presumably as a courtesy, as the required notice

had been filed with the trial court nine months before) that Stump’s counsel

filed a motion in limine to exclude the KRE 404(b) prior bad acts evidence due

to lack of adequate notice pursuant to KRE 404(c). The trial court denied

Stump’s motion and indicated it would admit evidence pertaining to the alleged

prior rape.

During trial, Sally testified as to Stump’s prior bad acts—specifically an

alleged rape that she had not reported to authorities. She testified that Stump

had previously raped her when she was twelve years old. She stated that

Stump had told her to go to his room, pull down her pants, and lie down on his

bed. She stated that he turned around and used a penis pump, and then laid

on her and held himself up. She testified that he put his penis “in” her, and,

once he had finished, that he went to the bathroom and she went to be with

her sister in a different room. The Commonwealth then asked Sally tf Stump

put his penis “on” her vagina, and Sally answered yes. In spite of the

Commonwealth’s inartful question given the fact that Sally had clearly stated

Stump had put his penis “in” her, Sally went on to make it clear that Stump

had done more than merely put his penis “on” her vagina. Sally indicated in

her testimony that she bled from the encounter and that it hurt more than the

second rape. Furthermore, Sally testified that she told Stump it hurt, but he

did not stop. She stated Stump also told her not to tell anyone what he had

done to her on this occasion.

Sally testified that she spent one weekend a month at Stump’s residence

prior to the first rape. However after, the first rape occurred, she said she did

not go back to Stump’s residence for a while. When she started visiting

Stump’s residence again, the charged rape occurred.

II. ANALYSIS

A. Prior Bad Acts

1. Motion in Limine

Stump alleges that the trial court erred when it overruled his motion in

limine concerning the admission of KRE 404(b) prior bad acts evidence. On

appeal, “[w]e will not disturb a trial court’s decision to admit evidence absent

an abuse of discretion.” Matthews v. Commonwealth, 163 S.W.3d 11, 19 (Ky.

2005) citing Partin v. Commonwealth, 918 S.W.2d 219, 222 (Ky. 1996). “The

test for abuse of discretion is whether the trial judge’s decision was arbitrary,

unreasonable, unfair, or unsupported by sound legal principles.”

Commonwealth v. English, 993 S.W.2d 941, 945 (Ky. 1999). Applying this test

to the case at bar, we will not overturn the trial court’s decision, as the trial

court did not abuse its discretion in denying’s Stump’s motion in limine and

admitting the evidence of the prior alleged rape.

Stump filed his motion to exclude evidence of uncharged crimes due to

the Commonwealth’s alleged failure to provide proper notice. The uncharged

crime in question is the alleged rape that Sally testified to. According to Sally,

on this occasion. Stump raped her when she was twelve using a penis pump

before inserting his penis into her vagina.

At the in-chambers hearing on this motion conducted prior to trial, the

Commonwealth argued that Stump had been put on notice, as allegations of

prior sexual assault and an approximate timeline for these assaults were

produced in discovery—and Stump was aware that the Commonwealth had

medical records referencing a prescription for the penis pump. Also, a notice

and motion to introduce evidence pursuant to KRE 404(b) filed on October 27,

2016, reflected the Commonwealth’s intent to introduce evidence of prior

sexual assaults Stump perpetrated against Sally.

Stump also argues that he was unfairly prejudiced by Sally’s testimony

in which she referred to the alleged prior rape. He contends that the

Commonwealth withheld the information of the alleged rape and the medical

records referencing a penis pump prescription in bad faith. However, Sally’s

allegation that Stump had sexually assaulted her on numerous occasions was

included in discovery. The Commonwealth also claims that Stump’s counsel

had visited its office and viewed the medical records referencing the penis

pump. During the nine months between the Commonwealth’s notice and

Stump’s motion in limine, he had ample opportunity to request additional

information regarding the allegations of uncharged sexual assault.

Stump maintains that he was not given adequate notice pursuant to KRE

404(c) to prepare his defense. KRE 404(c) reads:

In a criminal case, if the prosecution intends to introduce evidence pursuant to subdivision (b) of this rule as a part of its case in chief, it shall give reasonable pretrial notice to the defendant of its intention to offer such evidence. Upon failure of the prosecution to give such notice the court may exclude the evidence offered under subdivision (b) or for good cause shown may excuse the failure to give such notice and grant the defendant a continuance or such other remedy as is necessary to avoid unfair prejudice caused by such failure.

Here, the KRE 404(c) requirement that the Commonwealth give “reasonable

pretrial notice” of intention to introduce other criminal evidence was satisfied

as the fact that Sally alleged sexual assaults happening on numerous

occasions was included in discoveiy.

“The intent of [KRE 404(c)] is to provide the accused with an opportunity

to challenge the admissibility of this evidence through a motion in limine and

to deal with reliability and prejudice problems at trial.” Bowling v.

Commonwealth, 942 S.W.2d 293, 300 (Ky. 1997); Robert G. Lawson, The

Kentucky Evidence Law Handbook, § 2.25 (3rd Ed. 1993). This requires us to

examine the facts surrounding the admission of the evidence in question.

On August 12, 2012—nearly five years before trial—the Commonwealth

filed discovery materials containing a Kentucky State Police supplemental

report. This report details that Sally claimed that Stump had raped her in

April 2012 and that it had happened numerous times before. A crime

supplement document of the KSP records provides an approximate timeline

concerning Sally’s abuse as 2006-2008 and 2009-2012.

In Tamme v. Commonwealth, 973 S.W.2d 13 (Ky. 1998), Walker v.

Commonwealth, 52 S.W.3d 533 (Ky.2001), and Bowling, 942 S.W.2d 293, the

appellants all raised notice issues concerning the admission of KRE 404(b)

evidence. In those cases, we upheld the notice on “actual notice” grounds.

In Tamme, an alibi witness testified at the hearing on a motion for a new

trial that he had been with the appellant in Indiana on the day of the murders.

973 S.W.2d 13. The Commonwealth was able to discredit the alibi witness’s

testimony by establishing that he was incarcerated in the Barren County jail on

the day of the murders, and, thus, could not have been in Indiana with the

appellant as claimed. The alibi witness later pleaded guilty to perjury with

respect to this testimony. At retrial, the Commonwealth introduced evidence of

the witness’s perjury following the appellant’s Introduction of two new alibi

witnesses. This Court held that “[o]bviously, no prejudice occurred, because

Appellant had actual notice of this evidence and raised the KRE 404(b) issue

both in his own in limine motion and when the evidence was offered at trial.”

973 S.W.2d at 32 (other citations omitted).

In Walker, the appellant also argued that the Commonwealth failed to

provide reasonable notice under KRE 404(c) of its intent to introduce KRE

404(b) evidence at trial regarding a controlled buy that had occurred prior to

arrest. 52 S.W.Sd 533. The buy supplied the police with probable cause to

obtain a search warrant of the appellant’s residence. When executing the

warrant, police caught the appellant attempting to flush cocaine down the

toilet. This act was the basis of the appellant’s arrest. The Commonwealth did

not plan to introduce the evidence of the controlled buy until a witness (who

was supposed to testify that the appellant had sold crack cocaine on the day of

the search) failed to appear. This caused the Commonwealth to re-evaluate its

need to Introduce the controlled-buy evidence. The trial court admitted the

evidence only to show the appellant’s intent to sell. This Court held that the

trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting the evidence, as the

appellant was able to challenge the admissibility through a motion in limine on

KRE 404(b) grounds and the evidence was not unknown to the defense, thus

minimizing any surprise. The facts of Walker are similar to the case at hand,

as the evidence of Sally’s allegation that Stump had sexually assaulted her on

numerous occasions was contained in discovery, and, therefore, was known to

the defense.

The appellant in Bowling, also raised the issue of insufficient notice

pursuant to KRE 404(c). 942 S.W.2d 293. The evidence in that case regarded

testimony that identified the appellant as someone who had fired gunshots at a

witness three days after the murder of the victim in question. This Court

8

upheld the trial court’s oral ruling that the Commonwealth had furnished

discovery that supplied the appellant with notice. Further, this Court held that

no prejudice had occurred because the appellant had actual notice and raised

the 404(b) issue in his motion in limine. As in Bowling, Stump had actual

notice of the alleged prior sexual assault through discovery and also raised the

issue in his motion in limine filed before trial.

Just as in the cases discussed above, no prejudice occurred here by

admitting Sally’s testimony and the medical records in question—as Stump

had actual notice and had raised the issue in his motion in limine. The actual

notice was provided throughout discovery and in the documents providing an

approximate timeline for the alleged sexual assault and stating that Sally

claimed Stump had sexually assaulted her on numerous occasions.

Further, Stump was put on notice by the motion to introduce evidence

pursuant to KRE 404(b) that was filed on October 27, 2016, which stated that

the Commonwealth moved to introduce evidence that the defendant sexually

assaulted the victim on numerous occasions before the charged rape. To

reiterate, this motion was filed close to nine months before trial began. This

notice alone gave Stump adequate notice to prepare his defense. Additionally,

the Commonwealth emailed Stump a similar notice on July 21, 2017, regarding

evidence of other acts of sexual abuse by the defendant perpetrated upon the

victim.

9

We hold that Stump had adequate opportunity to prepare a defense in « anticipation of the Commonwealth’s introduction of evidence regarding the

uncharged alleged rape.

2. Prior Inconsistent Statement

Though unclear, it appears Stump attempts to argue that the trial court

abused its discretion in sustaining the Commonwealth’s objection regarding

prior inconsistent statement testimony. In trying to impeach Sally, Stump’s

counsel questioned her about her forensic interview with the Child Advocacy

Center. Defense counsel asked Sally if she had mentioned the previous rape

involving the penis pump during the interview. Sally testified that she had not,

as she was anxious that day and did not want to talk about it.

Following Sally’s answer, Stump’s counsel asked Sally to read a passage

from the transcript of her interview. The Commonwealth objected on the basis

that Stump was attempting to improperly impeach Sally and a bench

conference ensued. After the bench conference, Stump did not ask Sally any

further questions regarding the previous rape. As noted, Sally testified that

she had not discussed the previous rape during the interview and explained

her reasoning. This Court held in Bratcher v. Commonwealth that “statements

were not prior inconsistent statements as contemplated by KRE 613 because

[the witness] had already admitted that he lied at the prior suppression

hearing. Playing the videotape would have had no impeachment value and

would simply have been cumulative.” 151 S.W.3d 332, 342 (Ky. 2004).

10

In Bratcher, the appellant claimed that the trial court interfered with his

right of confrontation by disallowing the introduction of a witness’s prior

statement. The prior statement was a videotape of a suppression hearing. The

witness had admitted that he lied at said suppression hearing during his direct

testimony. The appellant wanted to use the videotape as evidence of a prior

inconsistent statement. However, the trial court refused to allow the appellant

to use the videotape. Since the witness had already admitted he lied, the

videotape contained no prior inconsistent statement and would likely confuse

the jury. Id.

Here, Sally reading a passage from the transcript lacked impeachment

value and would have merely been cumulative, as she had already admitted on

the stand that she was anxious and did not talk about the previous rape

during said interview. A prior statement cannot be deemed inconsistent if it

does not conflict with the witness’s testimony.

3. Admissibility of Evidence

While this issue also lacks clarity, Stump appears to argue that the

evidence of the prior rape was inadmissible. However, “[e]vidence of other

crimes, wrongs, or acts is admissible if relevant for some purpose other than to

prove character, such as proof of motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan,

knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or accident.” Tamme, 973 S.W.2d at

23: KRE 404(b)(1).

An exception allowing the introduction of 404(b) evidence exists when the

acts are admitted to prove the perpetrator’s opportunity to commit the crime.

11

Therefore, prior bad acts evidence showing that Stump had the opportunity to

rape Sally is admissible. See United States v. Blakeney, 942 F.2d 1001, 1017

(6th Cir. 1991). Through Sally’s testimony, the Commonwealth showed Stump

had the opportunity to rape Sally on both occasions Sally alleged at trial.

Sally testified that at the time the charged rape occurred, she was living

with her father and step-mother. She said that she would typically spend one

weekend a month at Stump’s residence before the uncharged rape she testified

about occurred. She further stated that she would be left alone with Stump

while his wife (her grandmother) was at work. The first rape occurred when

Stump was afforded this opportunity to access Sally outside the presence of

other adults. Slly testified that after the uncharged rape occurred, she quit

going to Stump’s residence for some time. Further, she stated that when she

returned to Stump’s residence after foregoing her weekend visits for a while,

the charged rape occurred. Sally’s testimony reflects that Sally’s grandmother

was not home on the day of the charged rape. This reflects Stumps

opportunity to commit the acts of sexual abuse.

Furthermore, “evidence of similar acts perpetrated against the same

victim are almost always admissible . . . .” Noel v. Commonwealth, 76 S.W.Sd

923, 931 (Ky. 2002). Applying that rule to the facts in Harp, this Court upheld

the trial court’s admission of evidence “regardless of whether the conduct was

specifically contained in the indictment against [the appellant]. [The appellant]

unsuccessfully sought to exclude the evidence of uncharged sexual contact

with [the victim].’’ 266 S.W.Sd 813, 822 (Ky. 2008).

12

The 404(b) evidence of prior bad acts in Harp included the appellant

exposing his genitals to the victim on multiple occasions. This Court reasoned

that: “we do not perceive that any prejudice suffered by Harp was sufficient to

overcome the general rule regarding admissibility of similar acts perpetrated

against the same victim. Thus, we find no error in the trial court’s decision to

admit the KRE 404(b) evidence in question.” Id. at 822-23 (emphasis added).

The standard quoted in Harp, that evidence of similar acts perpetrated against

the same victim is almost always admissible, is clearly applicable to the case at

hand as the two rapes are similar acts that occurred to Sally.

Therefore, even if the acts were not used to show Stump’s opportunity to

commit the charged act, the uncharged rape would have been admissible

evidence under Harp.

4. Closing Statements

The Commonwealth characterized the first alleged act of sexual abuse as

rape during its closing statement. The trial court sustained Stump’s objection

to this characterization, reasoning that it did not believe that Sally testified that

penetration had occurred in the uncharged rape.

Notably, Sally testified that Stump put his penis “in” her during this first

alleged (albeit uncharged) rape. Therefore, pursuant to her testimony,

penetration occurred. After Sally’s statement that Stump penetrated her, the

prosecutor said, “when you say he put his penis in me, you felt his penis on

your vagina.” Sally then detailed about how the abuse hurt and that it caused

13

her to bleed. Thus, the Commonwealth was not mistaken in referring to the

uneharged ineident as a rape.

Nonetheless, the trial court (mistakenly) did not think that SaUy had

testified as to penetration and admonished the jury that the Commonwealth’s

characterization of the prior sexual assault as a rape was inconsistent with

Sally’s testimony.

Stump asserts that this characterization of the prior bad act as rape

necessitates reversal. We disagree, as we have consistently held that opening

and closing arguments are not evidence and prosecutors have a wide latitude

during both. Stopher v. Commonwealth, 57 S.W.Sd 787, 805-06 (Ky. 2001). As

we held in Brown v. Commonwealth:

reversal is warranted “only if the misconduct is ‘flagrant’, or if each of the foUowing three conditions is satisfied: (1) proof of defendant’s guilt is not overwhelming: (2) defense counsel objected; and (3) the trial court failed to cure the error with a sufficient admonishment to the jury.” Matheney v. Commonwealth, 191 S.W.Sd 599, 606 (Ky. 2006) (quoting Barnes v. Commonwealth, 91 S.W.Sd 564, 568 (Ky. 2002). We use the Dickerson test to determine if the prosecutor’s comments were “flagrant”: “(1) whether the remarks tended to mislead the jury or to prejudice the accused; (2) whether they were isolated or extensive; (3) whether they were deliberately or accidentally placed before the jury; and (4) the strength of the evidence against the accused.” Dickerson v. Commonwealth, 485 S.W.Sd 310, 329 (Ky. 2016).

553 S.W.Sd 826, 837-38 (Ky. 2018). In this case, the evidence against Stump

was overwhelming. We find it difficult to characterize the Commonwealth’s

reference to the uncharged rape as rape as “misleading” or “prejudicial” based

on the entirety of the facts and circumstances of this case, as Sally did testify

that penetration had occurred.

14

In any event, the characterization here was not so egregious or

prejudicial as to require reversal—especially in light of the trial court’s

admonition correcting the characterization for the jury. Winstead v.

Commonwealth, 327 S.W.3d 386, 400 (Ky. 2010). Regarding admonitions, this

Court held in Johnson v. Commonwealth:

A jury is presumed to follow an admonition to disregard evidence and the admonition thus cures any error. Mills v. Commonwealth, Ky., 996 S.W.2d 473, 485 (1999) . . . There are only two circumstances in which the presumptive efficacy of an admonition falters: (1) when there is an overwhelming probability that the jury will be unable to follow the court's admonition and there is a strong likelihood that the effect of the inadmissible evidence would be devastating to the defendant, Alexander v. Commonwealth, Ky., 862 S.W.2d 856, 859 (1993); or (2) when the question was asked without a factual basis and was “inflammatory” or “highly prejudicial.” Derossettv. Commonwealth Ky., 867 S.W.2d 195, 198 (1993); Bowler V. Commonwealth Ky., 558 S.W.2d 169, 171 (1977).

105 S.W.3d 430, 441 (Ky. 2003).

After reviewing the record, we are not persuaded that the

Commonwealth’s statements were made in error (as the trial court was

mistaken that Sally had not testified regarding penetration). However, even if

the statement were error, any such error was cured as it is presumed the jury

was able to follow the admonition to disregard the Commonwealth’s

characterization to the prior abuse as rape during closing statements.

B. Missing Evidence Jury Instruction

Stump preserved this issue by tendering a written missing evidence jury

instruction pertaining to a forensic pelvic examination. The trial court denied

this Instruction, through an oral ruling, stating that the forensic pelvic

15

examination did not fall within the definition of missing evidence in this case.

We agree with the trial court.

While Stump argues that this is a matter of law that we should review de

novo, we disagree. We review this alleged error for an abuse of discretion. “[A]

trial court’s decision on whether to instruct on a specific claim will be reviewed

for abuse of discretion; the substantive content of the jury instructions will be

reviewed de novo.” Sargent v. Shaffer, 467 S.W.Sd 198, 204 (Ky. 2015). Here,

the trial court decided not to provide an instruction as to a specific claim. “The

trial court may enjoy some discretionary leeway in deciding what instructions

are authorized by the evidence, but the trial court has no discretion to give an

instruction that misrepresents the applicable law.” Id. at 204.

Stump argues that the jury should have been instructed regarding the

fact that Sally had the examination performed months after the charged rape.

Further, Stump states that he was “denied due process when exculpatory

evidence of obvious value was wasted by the Commonwealth or its agents when

the juvenile was not examined within the critical period of 96 hours to collect

[sic] real evidence of DNA or injury or confirm their absence.” He asserts this

amounted to missing evidence, necessitating his tendered instruction.

Here, Sally testified that she told her best friend who encouraged her to

tell a teacher. The charged rape occurred on April 14, and the record reflects

that Sally did not report it to an adult for nine days—when she told her teacher

and guidance counselor on April 23. In turn, the guidance counselor reported

the abuse to the Child Protection Hot Line. Given this timeline, it would have

16

been impossible for the Commonwealth to conduct an examination within the

critical 96-hour period following the rape.

The charged rape occurred on April 14, 2012. The state received notice

of the allegation of this rape on April 23, 2012. The forensic interview occurred

with the Child Advocacy Center on May 16, 2012, and the physical

examination occurred on June 8, 2012. Stump contends that this delay in

having the examination conducted was purposeful and favored the

Commonwealth, spoiling evidence in which the exculpatory value was clear.

Just as the trial court, we are not persuaded by Stump’s argument. It

was impossible for the Commonwealth to collect or preserve the evidence

within the 96 hours (4 days) demanded by Stump, because the rape was first

reported to an adult (the victim’s teacher) 9 days after it occurred. The forensic

pelvic examination was conducted on June 8, which preserved any evidence

that existed once the Commonwealth was notified of the crime. The trial court

correctly ruled that the forensic pelvic examination and the failure to conduct

the examination at an earlier date did not constitute missing evidence.

This Court held in Ordway v. Commonwealth:

The missing evidence instruction should be given when material evidence within the exclusive possession and control of a party, or its agents or employees, was lost without explanation or is otherwise unaccountably missing, or was through bad faith, rendered unavailable for review by an opposing party. When appropriately given, the missing evidence instruction allows the jury, upon finding that the evidence was intentionally and in bad faith destroyed or concealed by the party possessing it, to infer that the evidence, if available, would be adverse to that party or favorable to his opponent. University Medical Center, Inc. v. Beylin, 375 S.W.3d 783, 792 (Ky.2O12). When it is established that the evidence was lost due to mere negligence or inadvertence, which,

17

in effect, negates a finding of bad faith, the missing instruction should not be given. Id. at 791 (citing Mann v. Taser Intern., Inc., 588 F.3d 1291, 1310 (11th Cir.2009)).

391 S.W.3d 762, 793 (Ky. 2013). Stump has the burden of proving that the

Commonwealth acted in bad faith in its failure to procure the allegedly missing

evidence. Collins v. Commonwealth, 951 S.W.2d 569, 573 (Ky. 1997). As

stated above, the record does not reflect that Stump offered any evidence of the

Commonwealth acting in bad faith in regard to the forensic pelvic examination.

Therefore, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by rejecting the

requested jury instruction and did not deprive Stump of his due process rights.

Outcome: For the foregoing reasons, we affirm Stump’s conviction and sentence.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: