Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 03-08-2017

Case Style:

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ‐v.‐ AKEEM MONSALVATGE, EDWARD BYAM, DERRICK DUNKLEY

|

|

Case Number: 14‐1113‐cr(L)

Judge: Debra Ann Livingston

Court: UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Defendant's Attorney: JONATHAN I. EDELSTEIN

Description:

MoreLaw Receptionist Services

Never Miss Another Call With MoreLaw's Receptionists Answering Your Calls

Monsalvatge, Byam and Dunkley were convicted after a jury trial of

committing armed robberies of two Pay‐O‐Matic check‐cashing stores and of

conspiring to commit these crimes. As set forth below, the two robberies

differed in their modus operandi. In the first robbery, on February 24, 2010, three

bandana‐covered men, wielding guns, stole $44,039.73 from a Pay‐O‐Matic

located at 160‐30 Rockaway Boulevard in Queens, New York, with one of the

robbers gaining access to the protected area of the store by descending through

the roof. In the second robbery, on February 14, 2012, almost two years later,

three robbers stole $200,755.89 at gunpoint from a Pay‐O‐Matic located at 247‐12

South Conduit Avenue, also in Queens, New York. This time, however, the

robbers did not wear bandanas, but rather police‐uniform disguises and lifelike

“special‐effects” masks, and they accosted an employee in gaining access to the

store. And unlike in the first robbery, so as to remove any fingerprints or DNA, 1 The factual background presented here is derived from the testimony and evidence presented at trial. References in the form “Gov’t Ex. __” herein are to the Government’s exhibits.

5

one of the robbers poured bleach on the teller counter. At trial, the Government

played three of four The Town movie clips admitted by the district court (lasting a

total of one minute and seven seconds) for the jury. The Government argued

that Monsalvatge was familiar with The Town and admired it, and that the

co‐conspirators altered their modus operandi to carry out the second robbery in a

manner resembling robberies depicted in the movie.

A. The February 24, 2010 Robbery

The first Pay‐O‐Matic robbery occurred in the early morning hours of

February 24, 2010.2 That morning, Muhammed Hafeez was working as the

cashier at the Pay‐O‐Matic. His workspace, the cashier area, was separated

from the counter by a bulletproof‐glass divider and two locked doors. Hafeez

left to use the restroom, which was located at the back of the store, still behind

the secure cashier area. While he was in the bathroom, he heard a crash.

Upon leaving the restroom to investigate the disturbance, Hafeez saw a

robber (“Robber 1”) holding a gun and standing in the secure cashier area. The

crash Hafeez heard occurred when the robber gained entry to the store’s secure

area by descending through an air duct that had been pried open on the store’s 2 A surveillance camera captured the events of the robbery, which transpired between 3:24 and 3:57 a.m. See Gov’t Ex. 7; see also Gov’t Ex. 49 (surveillance video stills).

6

roof, leaving a large hole in the store’s ceiling. The robber wore a black hooded

sweatshirt with jeans; his face was covered with a black bandana; and he wore

blue gloves with white text. The robber aimed his gun at Hafeez, directed him

to lie on the floor face down, and handcuffed him.3

A second robber (“Robber 2”) appeared on the scene in the customer area

of the store. Robber 2 also wore jeans and had his face covered but, unlike

Robber 1, he wore an orange construction vest with yellow stripes over a blue

jacket. In order to confer with Robber 2, Robber 1 left the secure cashier area of

the store, with the door locking behind him and leaving Hafeez by himself. The

robbers, realizing they were now locked out of the secure cashier area,

demanded that Hafeez open the door. Hafeez refused. The robbers attempted

to force open the door but failed. At that point, Robber 1 left the store. Robber

2 stayed behind, pointing the gun at Hafeez through the window while making

calls on his cell phone.4

3 The Government introduced evidence at trial to show that Monsalvatge’s DNA was recovered from the handcuffs used on Hafeez and left at the crime scene — evidence that contradicted Monsalvatge’s statements to police and to a grand jury that he had not been in contact with handcuffs since 1996. 4 At trial the Government introduced cellular telephone records that established, inter alia, that between 2:04 a.m. and 3:58 a.m. on the morning of the robbery, Monsalvatge and Byam’s cell phones exchanged more than 13 calls, all of which were

7

Robber 1 crashed through the ceiling again, gaining entry to the cashier

area. He removed the money from the cashier’s drawers and put it in his bag.

Robber 2 continued to use his cell phone. At that point, Robber 1 asked Hafeez

to open the safe. Hafeez responded that he did not know the combination to

the safe. The scene turned violent. Robber 1 began to beat Hafeez with a

metal chair. Robber 2 attempted to pass a gun to Robber 1 through a slot in the

teller window, but the slot was not wide enough to allow the gun to pass from

the customer area, where Robber 2 stood, to the cashier area, where Robber 1

stood. Robber 2 made another phone call.

Soon, a third robber (“Robber 3”) entered the store. Robber 3’s

appearance was not clearly captured on the surveillance footage. He wore dark

clothing, a dark jacket, and dark pants. In the store lobby, Robber 3, who had a

gun, switched his weapon with Robber 2. Robber 2 handed the apparently

slimmer gun to Robber 1 through the slot in the teller window. Robber 3 left the

store.

Robber 1, now again armed, questioned Hafeez about the safe, asking him

who would know the combination if not him. When Hafeez told Robber 1 that

routed through a cell phone tower located just one block away from the Rockaway Boulevard Pay‐O‐Matic.

8

his supervisor had the combination, Robber 1 demanded that Hafeez call the

supervisor, which Hafeez did. Hafeez’s supervisor, however, would not give

Hafeez the combination to the safe. After that unsuccessful call, Robber 1 threw

Hafeez’s cell phone into one of the drawers. Robber 1 told Hafeez to move to

the restroom. While Hafeez was in the bathroom, Robber 1 left the store using

the emergency exit, and Robber 2 left through the front door. The robbers

absconded with $44,039.73.

B. The February 14, 2012 Robbery

As already noted, the second robbery occurred almost two years later, on

February 14, 2012, also at a Queens Pay‐O‐Matic.5 At 7:56 a.m., a black Ford

Explorer SUV pulled into the parking lot of the Pay‐O‐Matic check‐cashing store

on South Conduit Avenue in Queens. What appeared to be a bag covered a

damaged right rear window of the SUV, which also bore a distinctive dent on the

front passenger side of its bumper. Fifteen minutes later, just past eight o’clock

in the morning, Liloutie Ramnanan, a teller at the Pay‐O‐Matic, drove her car

into the parking lot. Ramnanan saw three people in the SUV. As Ramnanan

walked toward the store and passed the vehicle, the three stepped out of the car.

5 A surveillance camera captured the events of this robbery as well. See Gov’t Ex. 4; see also Gov’t Ex. 2 (surveillance video stills).

9

They appeared to be white‐ or light‐skinned men. All three men,

however, also appeared to have brown lips. Ramnanan assumed they were law

enforcement officials because they wore police attire: blue police jackets with

hoods (bearing the police shield on the left side of the chest), police badges, and

sunglasses. Two men wore baseball caps, but one did not—the third who did

not wear a baseball cap appeared to be a bald man with a goatee.6

The goateed man suddenly approached Ramnanan, stopped her, and

asked whether she worked at Pay‐O‐Matic. Ramnanan responded that she did.

At that point, he pulled out three papers with photographs of houses on them.

According to Ramnanan, he showed her one of the photographs, and asked

whether she “kn[ew] this photo of this house.” Joint App’x 701. She

answered, yes, recognizing the house in the photograph as her own.7 He then

6 The Government adduced testimony at trial from the owner of a special‐effects mask manufacturing company who explained that the robbers wore lifelike masks and that he had sold three such masks to Byam in October 2011. 7 Surveillance footage of the robbery in progress depicted one of the robbers later dropping an item which turned out to be the photo of Ramnanan’s house. It was stamped “Walgreens” on the back side, and bore both a store number and the date “12‐3‐11.” Subsequent investigation revealed that this particular Walgreens was near Byam’s residence, and that a “Byam, E.,” providing a telephone number that matched Byam’s, had placed the photograph order. Surveillance video from the pharmacy depicted Byam dropping something off at the photograph counter on December 3, 2011, and picking something up later that day.

10

asked her who was inside the store and Ramnanan realized, “this is a hold up.”

Id.

The goateed man directed Ramnanan to walk inside the store. Inside,

there were two other people: a customer and the outgoing overnight teller

named Sean Anderson. Anderson stood in a secured teller area. That area was

protected by bulletproof glass and separated from the lobby by two doors that

could be unlocked only from the teller area. Anderson noticed that the men

wore gloves and that one of the pairs of gloves was blue with white text. The

goateed man, upon entering the store, demanded that Anderson open the door.

Anderson obliged, and the goateed man directed Ramnanan along with the two

other robbers inside that space.

Inside the teller area, one robber emptied a safe and put the money into a

black bag. The other robber demanded at gunpoint that Anderson and

Ramnanan lie down on the floor. The armed robber emptied the teller drawers

and splashed the teller counter with a liquid that smelled like bleach.8 The three

8 Police later recovered an empty juice bottle at the scene that still smelled of bleach. Both Ramnanan and Anderson testified that their apparel was splattered with the liquid during the crime, causing the clothing items, where splattered, to turn white.

11

robbers then left the Pay‐O‐Matic with the cash, driving off in the SUV.9 In

total, the robbers stole $200,755.89.

Bank records showed that thousands of dollars of cash were deposited into

Dunkley’s account shortly after the February 14, 2012 robbery. Monsalvatge

opened a new account on February 15, and shortly thereafter made several large

cash deposits. Within months, Monsalvatge and Byam also took a trip to

Cancun. Records show, and employees from various luxury goods retailers

testified, that each of the defendants spent thousands of dollars on high‐end

goods during the spring and summer of 2012.

* * *

On August 21, 2012, Monsalvatge was arrested pursuant to an arrest

warrant.10 Shortly thereafter, Byam, while in his apartment, was also arrested

pursuant to a warrant. Upon arrival, the arresting officers brought Byam into

9 By checking addresses associated with Byam’s family and friends, investigators later located the SUV, with both the damaged rear window and the dent, in the driveway of a house in Queens. Police officers inspected the vehicle, but the SUV was thereafter sold to a scrap yard and destroyed when police did not seize it. Byam’s girlfriend testified at trial that the car was given to her by her stepfather and that Byam had keys to the car and used it. She also testified that she instructed Byam to get rid of the car after learning that police had examined it. 10 Monsalvatge was driving at the time of his arrest and, from the car, the police seized a pair of work gloves, a police scanner, and Monsalvatge’s cell phone.

12

the apartment building hallway and proceeded to conduct a protective sweep of

the apartment.11 The next day, Derrick Dunkley purchased a bus ticket from

New York City to Hartford, Connecticut. Approximately one month later, law

enforcement officers located and arrested Dunkley at his aunt’s house in

Hartford.12

11 The police seized the following: a partially completed Pay‐O‐Matic employment application, which bore Byam’s name and address; a black bag (believed to be a “robbery bag”) that was later found to contain a mask, walkie‐talkies, a bottle of bleach, and photographs; and a small cloth bag that was later found to contain a BB gun. Later, during the pre‐trial proceedings, Byam moved to suppress this evidence as the fruit of an unlawful search. The district court found that the agents were lawfully in Byam’s apartment and were justified in conducting a protective sweep. The district court concluded, however, that “the protective sweep got out of hand” and suppressed all of the evidence seized from Byam’s apartment with one exception: the Pay‐O‐Matic application, which, the district court found, had been in plain view and was “immediately recognized by one of the agents.” Joint App’x 393‐94; see also Gov’t Ex. 73. 12 During a consensual search of the residence, the officers seized a laptop computer, identification cards, credit cards, a hat, safe deposit box keys, documents, and two cell phones. A search of Dunkley’s computer showed multiple recent Internet searches about the federal criminal justice system. Specifically, Dunkley searched for information relating to the following questions and phrases: “Does a subpoena mean you’re under arrest?”; “If evidence used in a federal court case was on your property can you be held?”; “Evidence against you on someone else’s property”; and “Process it takes to bring someone to trial for federal crime.” Joint App’x 2264‐68. A search of Dunkley’s computer also uncovered a search for “NYPD jackets.” Id. at 2267.

13

II. Procedural History

On January 4, 2013, a grand jury indicted Monsalvatge, Byam, and

Dunkley, charging each of them with Hobbs Act robbery conspiracy, in violation

of 18 U.S.C. § 1951(a) (Count One); Hobbs Act robbery on February 24, 2010, in

violation of 18 U.S.C § 1951(a) (Count Two); unlawful use of a firearm in a crime

of violence in connection with the February 24, 2010 robbery, in violation of 18

U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(ii) (Count Three); Hobbs Act robbery on February 14, 2012,

in violation of 18 U.S.C § 1951(a) (Count Four); and unlawful use of a firearm in a

crime of violence in connection with the February 14, 2012 robbery, in violation

of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(ii) (Count Five).

A. Pre‐Trial Proceedings

The district court considered a number of motions in advance of trial. As

relevant here, the Government filed a motion in limine concerning The Town, a

2010 crime drama about a group of Boston bank robbers.13 The robberies in the

film bore certain similarities to the charged 2012 robbery, and the Government

had evidence that at least one of the defendants had seen and admired the film.

13 THE TOWN (Warner Bros. Pictures 2010). The Town, released on September 17, 2010, is based on Chuck Hogan’s 2007 book Prince of Thieves. Ben Affleck directed, co‐wrote, and starred in the film. The film grossed more than $154 million at the box office, and Jeremy Renner earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor for his performance.

14

In its motion, the Government requested to play for the jury at trial film clips

from The Town. These clips would serve “as evidence regarding the genesis of

the defendants’ modus operandi in the 2012 robbery and to explain the change in

modus operandi between robberies committed in 2010 and 2012.” Joint

App’x 406.

The first clip (“Clip 1”) is nine seconds long. See Gov’t Ex. 79 (Clip 1). It

begins by showing two investigators outside a Harvard Square bank that has

been robbed. They both wear navy‐blue jackets, one with a hood. One, in bold

letters, reads “POLICE” on the back, while the other reads “FBI.” The labels

“POLICE” and “FBI” appear in smaller letters on the front, left sides of the

jackets as well. As they enter the crime scene, the police investigator tells the

FBI agent that the perpetrators had “bleached the entire place for DNA,” which

“kills all the clothing fibers so [the investigators] can’t get a match.” Id. at

0:05‐0:09.

The second clip (“Clip 2”) is nine seconds long. See Gov’t Ex. 79 (Clip 2).

There are a number of robbers — four, it seems — who wear black hooded

sweatshirts and elaborate masks. The masks depict blue skulls with hanging

blue dreadlocks. For one second, one of the robbers is shown to be holding an

15

assault rifle14 — but only the butt of the gun appears, because the rest of it is

cropped at the bottom of the frame. Id. at 0:01. The mise‐en‐scène is difficult to

absorb in nine seconds, but the mood is tense: in the midst of the robbery, the

perpetrators realize there are people gathering outside the bank doors. One

robber says, “We gotta go.” Id. Another yells, “Let’s go!” Id. at 0:02. For two

seconds, the robber holding the weapon runs across the frame — the firearm is

visible, but blurred by the movement. A robber yells, “Let’s bleach it up! Let’s

bleach it up!” Id. at 0:04‐0:06. The robbers then pour bleach on the bank

teller’s counter as the clip ends.

The third clip (“Clip 3”) is twenty‐one seconds long. See Gov’t Ex. 79

(Clip 3). The scene opens with a closely framed image of one of the robbers,

played by Ben Affleck, who appears stern. He is sitting in the second row of a

van with the other robbers as they drive through the North End neighborhood of

Boston. They are on their way to commit a robbery. A police scanner discloses

the location of the authorities to the robbers. The driver advises the rest of the

group, “Say your prayers; here we go.” Id. at 0:08‐0:09. At that point, the

14 Both the Government and Monsalvatge characterize this weapon as an “assault rifle.” We understand, however, that this is a technical term, and we do not have any authoritative source that indicates the particular kind of weapon the fictional scene seeks to invoke. Nevertheless, for ease of reference, we adopt the parties’ terminology herein.

16

robbers, beginning with Affleck’s character, put on masks which disguise them

as elderly nuns. These masks show excessively wrinkled, sagging skin. The

masks have holes for the robbers’ real eyes and mouths — through which the

audience can see a bit of the robbers’ actual skin. For the final four seconds of

the clip, the audience sees a robber through the van’s window. The robber is

now masked as an older nun and holding an assault rifle. Only the top half of

the weapon is visible.

The fourth and final clip (“Clip 4”) is thirty‐seven seconds long. See Gov’t

Ex. 79 (Clip 4). This scene shows one of the robbers dressed as a police officer,

knocking on the door of the “cash room” at Fenway Park. He wears a dark‐blue

jacket (bearing the police department crest on the shoulder), a cap, a face scarf or

bandana, and sunglasses. On the left side of the front of the jacket, the robber

wears a police badge. He knocks on the locked door of the secured cash room.

He reveals to the employees on the other side that he knows their home

addresses and family members’ names, and that there are “men outside [their]

homes.” Id. at 0:28‐0:31. Their wives, the robber advises, would want them to

open the door. They do so, and the robber walks through the threshold

pointing a handgun.

17

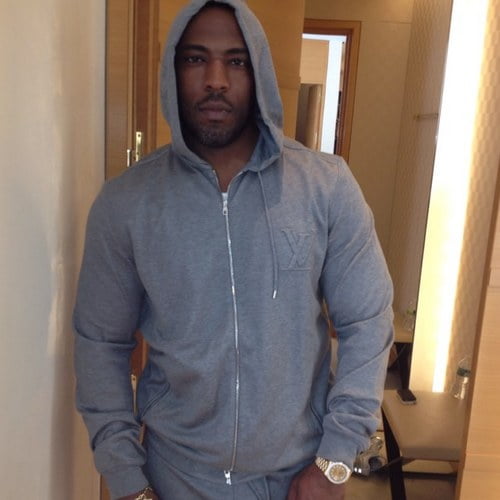

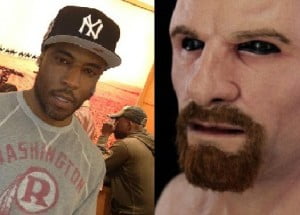

The Government sought to admit the film clips as relevant because, given

the similarities between the actions depicted in these scenes and the February

2012 robbery, the clips helped to explain why the 2010 and 2012 robberies had

proceeded differently. The similarities included: (1) pouring bleach on the bank

surfaces; (2) threatening an employee by revealing knowledge of the employee’s

home address; (3) wearing police badges, uniforms, and sunglasses; and (4)

wearing masks. In connection with its motion, the Government submitted an

iPhone photograph that showed Monsalvatge standing next to Byam and

wearing a t‐shirt with a silk‐screened image of one of the masked robbers from

Clip 3 of The Town. The Government also included text messages showing that

Monsalvatge had designed and custom‐ordered the t‐shirt at a mall.15 Dunkley

and Byam each raised a Federal Rule of Evidence 403 objection in their papers

opposing the Government’s motion in limine. The district court granted the

Government’s motion to admit the evidence. In doing so, the district court

explained that it had “looked at the clips” and noted that Monsalvatge had “a

T‐shirt . . . depicting a particular still scene from th[e] movie.” Joint App’x 643.

15 See Gov’t Ex. 120 (text message of Mar. 30, 2012, five weeks after the second robbery) (“Imma try n make it da mall 2 day so 4 da fly t it’s black wit white sleeves. N 4 da nun white wit da black sleeves.”).

18

On that basis, the district court “underst[ood]” the Government’s theory and

granted the motion. Id.

B. Trial Proceedings

The trial began on July 30, 2013. As part of the extensive proof at trial,

which included both surveillance footage of the two robberies and testimony

from Hafeez, Ramnanan, and Anderson, the Government introduced evidence

that all three defendants had frequented Pay‐O‐Matic cash‐checking stores

during the period of the alleged conspiracy and that each defendant’s cell phone

records showed a flurry of communications among the defendants surrounding

19

each of the robberies.16 Montsalvatge’s cell phone also contained photographs

and incriminating text messages among the three defendants.17

Specifically as to the February 24, 2010 robbery, the Government

introduced forensic evidence showing that Monsalvatge’s DNA was found on

the handcuffs used on Hafeez. Specifically as to the February 14, 2012 robbery,

the Government adduced testimony from digital retailers and manufacturers

regarding the defendants’ purchase of law enforcement paraphernalia and

lifelike masks worn during the robbery.18

16 The summary order published in tandem with this opinion details the phone calls exchanged between all three phones surrounding the February 24, 2010 robbery. 17 Some of the text messages between the three defendants referenced wealth and included images of money and various luxury goods. Other text messages, particularly those sent in the month following the 2012 robbery, featured more incriminating language. See Joint App’x 2306 (“Start getting y’alls mind back on work and excellent execution so we can be rich forever, rich forever.”); id. at 2305 (“[Y]ou passed the steal balls tst [sic]. You have the smarts and you are open to advice. If you stay disciplined, dedicated, desire, and respect what you do, I guarantee you will be a multimillionaire by the time you are 25, fact.”); see also Gov’t Ex. 122 (text messages between defendants). Particularly of note is a March 14, 2012, text message from Byam to Monsalvatge that states: “[T]hey taking DNA for misdemeanors now, shit crazy,” to which Monsalvatge responded, “[B]leach is a niggas best friend.” Joint App’x 2306; see also Gov’t Ex. 122. 18 A retailer testified that on November 19, 2011, an online user purchased three NYPD navy‐blue rain jackets that were hooded, zippered, and had an police department shield and read “NYPD” on the chest. The jackets were shipped to “Derrick Dunkley” at Dunkley’s residence. Another digital retailer testified that

20

At trial, the Government introduced the four clips from The Town into

evidence, which the district court admitted over objections by all three

defendants. The Government then played three of the four clips for the jury.

Before playing the clips, the district court provided an instruction to the jury:

“Folks, this is a movie, all right. It’s make believe. Anything that you hear on

this movie is not before you for the truth of it. This is Hollywood and not

Brooklyn federal court, so we’ll leave it at that for the time being.” Joint

App’x 1075. A Government witness, an investigating detective, highlighted

aspects of the clips as they were played for the jury.

The Government began by playing Clip 2 — the nine‐second‐long excerpt

depicting the robbers pouring bleach on the counter — for the jury. After

during the same month he sold three leather NYPD‐style badge holders to a user who had Dunkley’s address associated with the account. The owner of a lifelike special‐effects masks manufacturing company testified that Byam had purchased three special‐effects masks from his company on October 25, 2011. The masks were marketed as “Mac the Guy” masks with eyebrows, and one also had a goatee. Byam purchased the masks with a prepaid credit card, and the masks were ordered and delivered to the address of Monsalvatge’s girlfriend, with whom Monsalvatge lived. Byam later e‐mailed the manufacturer, stating that he was “extremely pleased” with the masks and asked for guidance about how to wear them. At the Government’s request, the company manufactured a “Mac the Guy” mask to the same specifications as the goateed mask Byam ordered. The company’s owner modeled it for the jury. Significantly, the owner testified that a person’s real lips are sometimes visible when wearing the mask. Last, he testified that, when he reviewed surveillance photographs from the 2012 robbery, he could tell that one of the robbers was wearing a “Mac the Guy” mask with a goatee.

21

playing the clip, the witness described the clip as showing “the perpetrators

robbing a bank and in th[e] container it contained bleach and they are pouring it

by the drawers and the teller area where they possibly touched.” Id. at 1076.

Next, the Government played Clip 4 for the jury. This

thirty‐seven‐second‐long excerpt showed, as the witness testified, a perpetrator

dressed as a police officer revealing to the employees that he knew personal

details about their lives. The witness explained that the character “knew [the

employees’] routines, he knew who their family were. He basically threatened

them if they were going to make a distress call, that their family would get

called.” Id. at 1077.

Last, the Government played Clip 3 for the jury. This

twenty‐one‐second‐long clip showed the robbers in a van with two of them

putting on a lifelike mask as part of a nun disguise. In conjunction with this

clip, the Government introduced into evidence the photograph of Monsalvatge

wearing a t‐shirt that depicted the image from that scene: the robber wearing the

lifelike nun mask. Byam is standing next to Monsalvatge in the photograph.

The Government later introduced into evidence text messages indicating that

Monsalvatge had custom‐ordered the t‐shirt at a mall.

22

In total, the Government played one minute and seven seconds of The

Town for the jury. The next day, the Government requested that the district

court provide the jurors an additional instruction regarding the movie clips. It

asked that the district court instruct the jury that “there were [no] actual people

outside of . . . Ramnanan’s home as was stated in the film and that the weapons

that were used in the particular robbery shown in the clip were large assault‐like

weapons. And that there’s no contention here that those types of weapons were

used in the robbery.” Id. at 1230. The robbers on trial, the Government

explained, used semiautomatic pistols. The Government sought this additional

instruction “[j]ust for the sake of making sure that there’s no confusion.” Id.

Later that day, the district court provided the additional instruction the

Government had requested:

[L]et me take you back to yesterday for just a moment. You will recall, I think it was yesterday, you saw clips from a movie. The movie is entitled . . . “The Town.” During those clips you may have noticed that actors were using these very fierce‐looking assault weapons. There is no evidence in this case nor is there an allegation in this case that such weapons were used; I want to make sure you understand that. There is also a scene that you may have noticed where the claim was that the perpetrators of the crime had somebody outside the house of some of the victims during the course of the crime; again, no such allegation in this case, and you’ll hear no proof to that effect in this case. I just want to make sure there is no misunderstanding.

23

Id. at 1307.

With that, the film clips were not mentioned again until summations,

when the Government described for the jury the different techniques the robbers

had used in the second robbery and stated, “we have an idea where they got

those techniques.” Id. at 2426. The Government explained:

You saw clips from a movie, The Town. You saw criminals being portrayed in that movie pouring bleach on surfaces to destroy DNA, using police uniforms, using a knowledge of victim’s homes to make sure that people would do what they wanted them to do. In one of those clips you hear a police scanner, so they can keep track of whether law enforcement is responding. Now, we know the defendants knew about that movie. Akeem Monsalvatge had a shirt depicting one of the scenes we watched, a shirt that he had made, an inside joke. But how did the techniques line up? They used bleach during their robbery. You recall the video, one of them clearing out the cash drawers and pouring the bleach from a bottle he had brought with him. We know it was bleach. The victim said it smelled like bleach. When it got on their clothing it created white spots. And we saw this text message yesterday, from Edward Byam to Akeem Monsalvatge, they taking DNA for misdemeanors now, shit crazy. Then the response, that bleach, it’s N‐I‐G‐G‐A‐S best friend. Keep in mind when Akeem Monsalvatge was sending that text message he had already been arrested for the 2010 robbery. He had already been told that his DNA was found at the scene. He certainly thinks bleach would be his best friend. What about the police uniforms? Yeah, they did that too. Knowledge of a victimʹs home, a threat that everyone would understand, they know where I live. What about the police scanner? You can see it here in his hands. And you can see it here

24

in Government Exhibit 62, seized from Akeem Monsalvatge, and when it was seized what station was it set to, fire and police.

Id. at 2426‐28.

During Monsalvatge’s summation, his counsel sought to diffuse the

Government’s theory that The Town accounted for the robbers’ change in modus

operandi. He told the jury that “[w]hen you look at the February 24th, 2010

robber, it’s like the Three Stooges, these guys don’t know what they are doing,

they get locked out. They are coming through the ceiling twice. . . . And they

are saying these three guys, that’s the team from 2010.” Id. at 497. By contrast,

the February 24, 2012 robbers appeared to be a “well[‐]oiled machine,” escaping

in three minutes with more than $200,000. Id. Incredulously, he concluded,

“But you know what the key is, the key is they saw the movie The Town, so they

got it all right.”19 Id. at 2498.

The district court proceeded to charge the jury. After deliberations, the

jury returned guilty verdicts against each of the three defendants on all five

19 Separately, counsel for Dunkley, in his summation, emphasized that there was no evidence that Dunkley had seen The Town. Dunkley’s counsel told the jury that the Government was “suggest[ing] that this bumbling pack of robbers in 2010 all of a sudden become [sic] this incredibly sophisticated group of robbers because they have seen a movie. If that’s the case, you can just watch a movie about brain surgery tomorrow and, you know, perform a flawless brain surgery on Saturday.” Joint App’x 2526. Byam’s counsel in his summation claimed that the Government used the movie clips to “dress[] the case . . . up.” Id. at 2474.

25

counts. On April 4, 2014, the district court sentenced each defendant to

thirty‐two years of imprisonment, five years of supervised release, $240,795.62 in

restitution, and a $500 special assessment.

DISCUSSION

We review a district court’s evidentiary rulings over objection for abuse of

discretion. United States v. Cuti, 720 F.3d 453, 457 (2d Cir. 2013). We review

such rulings deferentially, “mindful of [a district court’s] superior position to

assess relevancy and to weigh the probative value of evidence against its

potential for unfair prejudice.” United States v. Abu‐Jihaad, 630 F.3d 102, 131 (2d

Cir. 2010); see also 11 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 2885 (3d

ed. 1998) (describing a district court’s “wide and flexible[] discretion” in

“questions of admissibility of evidence”). Indeed, “[w]e will reverse an

evidentiary ruling only for ‘abuse of discretion,’ which we will identify only if

the ruling was ‘arbitrary and irrational.’” Abu‐Jihaad, 630 F.3d at 131 (citation

omitted) (quoting United States v. Dhinsa, 243 F.3d 635, 649 (2d Cir. 2001)).

At issue here is the district court’s admission of the movie clips from The

Town into evidence. On appeal, Monsalvatge, joined by Dunkley, contends that

the district court abused its discretion in admitting these clips into evidence and

26

allowing the Government to play three of them — lasting a total of one minute

and seven seconds — for the jury. For the following reasons, we disagree.

* * *

Evidence is relevant if “it has any tendency to make a fact more or less

probable than it would be without the evidence” and if “the fact is of

consequence in determining the action.” Fed. R. Evid. 401; see also Abu‐Jihaad,

630 F.3d at 131. “Evidence need not be conclusive in order to be relevant.”

United States v. Schultz, 333 F.3d 393, 416 (2d Cir. 2003) (quoting Contemporary

Mission v. Famous Music Corp., 557 F.2d 918, 927 (2d Cir. 1977)). A district court

“may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed

by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the

issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting

cumulative evidence.” Fed. R. Evid. 403. But in reviewing a district court’s

Rule 403 ruling, we “generally maximiz[e] [the evidence’s] probative value and

minimiz[e] its prejudicial value.” United States v. LaFlam, 369 F.3d 153, 155 (2d

Cir. 2004) (per curiam) (first and third alterations in original) (quoting United

States v. Downing, 297 F.3d 52, 59 (2d Cir. 2002)).

27

Here, the district court properly concluded that the clips were, indeed,

relevant under Federal Rule of Evidence 401. See Schultz, 333 F.3d at 416 (noting

that “[d]eterminations of relevance are entrusted to the sound discretion of the

trial judge”). The clips, in conjunction with other evidence, tended to make

more probable the factual inference that the 2010 and 2012 robberies (which

otherwise bore few similarities in modus operandi beyond the number of robbers

and the choice of targets) were part of the same conspiracy. The 2010 robbery,

as Dunkley’s counsel pointed out, was clumsily committed by a “bumbling pack

of robbers” who gained entry to the Pay‐O‐Matic by descending through the

ceiling. Joint App’x 2526. In contrast, the 2012 robbery was swiftly and

efficiently executed in a matter of minutes by robbers who accosted a store

employee. More importantly, the second robbery bore a different set of

characteristics: namely, the use of disguises — police uniforms — and lifelike

special‐effects masks, along with bleach to ensure the robbers left behind no trace

of DNA. The The Town clips (along with evidence that at least Monsalvatge and

Byam were aware of the movie and that Monsalvatge admired it sufficiently to

have a t‐shirt specially made to depict a The Town scene) helped to show that the

28

defendants’ modus operandi changed because they decided to incorporate ideas

from the movie into their method for committing robberies.

In February 2010, when the first robbery occurred, The Town was still seven

months away from its wide‐release date. But, by the second robbery in

February 2012, the film had long been available to the public. The 2012 robbery

bears a remarkable — even obvious — resemblance to multiple aspects of the

clips from The Town. In fact, nearly every distinctive aspect of the 2012 robbery

can be traced to the film. The robbers’ disguises, with minor differences, appear

to combine the navy‐blue police jacket with a hood and text detail on the front

left side of the jacket in Clip 1 and the sunglasses and badge in Clip 4. The idea

for special‐effects masks imitating real skin is in Clip 3. The idea to use bleach

to eliminate traces of DNA is in Clip 2 (and the effects of using bleach are

explained in Clip 1). Threatening an employee by revealing knowledge of a

home address is in Clip 4. That is every key facet of the 2012 robbery. Taken

individually, each of these elements might not be sufficiently distinctive to raise

a connection to the film. But taken together, as they occurred here, the

attributes of the 2012 robbery are clearly connected to the film.

29

Government Exhibits 99 and 120 make that connection even sharper. The

Government submitted an iPhone photograph that showed Monsalvatge

standing next to Byam and wearing a t‐shirt with a silk‐screened image of one of

the masked robbers from The Town — specifically, a still frame of the

nun‐costumed robber in Clip 3. See Gov’t Ex. 99. And this was not an

ordinary t‐shirt that a fan might purchase at a retail store. Rather, the

Government also introduced evidence to show that Monsalvatge designed and

custom‐ordered this t‐shirt. See Gov’t Ex. 120. This would have been a

distinctive sartorial choice for Monsalvatge at the time. The Government

adduced testimony at trial from employees of luxury good retailers — including

Fendi, Gucci, Ralph Lauren, Christian Louboutin, and Louis Vuitton — that the

defendants spent thousands of dollars at these stores during the spring and

summer of 2012. Despite this apparent taste for haute couture, Monsalvatge, in

March 2012, approximately five weeks after the second robbery, went to the mall

and custom‐ordered a t‐shirt depicting a scene from The Town. He later posed

with Byam for a photo wearing that shirt.

Monsalvatge states, in conclusory fashion, that the clips are prejudicial.

But he does not show how any potential for prejudice arising from the

30

introduction of these clips outweighed their evident probative value.

Monsalvatge does not even identify any specific prejudicial potential that these

clips carried beyond the fact that they “invited the jury to speculate that this was

a copycat crime.” Monsalvatge Br. 48. It is unclear — and Monsalvatge does

not explain — what effect characterizing the robbery as a copycat crime would

have on the jury.

In any event, the movie clips here do not have the sort of “strong

emotional or inflammatory impact” that would “pose a risk of unfair prejudice

because [they] ‘tend[] to distract’ the jury from the issues in the case and . . .

[might] arouse the jury’s passions to a point where they would act irrationally in

reaching a verdict.” United States v. Robinson, 560 F.2d 507, 514 (2d Cir. 1977)

(quoting Fed. R. Evid. 404 advisory committee note). First, they are very short.

Two clips last nine seconds, one lasts twenty‐one seconds, and another lasts

thirty‐seven seconds. They are so short because they are narrowly tailored to

show only the parts of the movie that are relevant to the 2012 robbery. The clips

depict no violence: the robbers do not hurt anyone on the screen. Granted, the

robbers do carry assault rifles in two of the clips, but those firearms appear for a

total of only seven seconds (in Clip 2, for one and two seconds, and, in Clip 3, for

31

four seconds). Further, in each instance, the weapons are either partially

cropped by the frame or blurred by the action. In the little dialogue that occurs

in the clips, moreover, the robbers appear to be the film’s protagonists.20 With

all this in mind, it is difficult to see how these clips could “unfairly . . . excite

emotions against the defendant[s].” United States v. Massino, 546 F.3d 123, 133

(2d Cir. 2008) (per curiam) (quoting United States v. Figueroa, 618 F.2d 934, 943 (2d

Cir. 1980)).

Critically, moreover, the district court took steps to minimize any potential

for prejudice that might exist. First, the district court gave not one but two

curative instructions. It initially instructed the jury: “Anything that you hear on

this movie is not before you for the truth of it.” Joint App’x 1075. The next

day, the district court further instructed the jury about two differences between

the 2012 robbery and the movie clips. It explained: “There is no evidence in

20 More broadly, for anyone who saw this popular movie, the robbers in the movie are classic anti‐heroes: they might break the law, but they are nevertheless the film’s protagonists and sympathetic characters. See, e.g., Anthony Lane, Actor’s Dilemma: “The Town” and “Jack Goes Boating,” NEW YORKER, Sept. 20, 2010, at 120, 120‐21 (“Affleck . . . plays the hero, Doug MacRay . . . . Affleck the movie director makes you truly, badly want his bunch of ne’er‐do‐wells to pull off their heists without a scratch, and you can’t ask for much more than that.”); A.O. Scott, Bunker Hill to Fenway: A Crook’s Freedom Trail, N.Y. TIMES, Sept. 16, 2010, at C2 (“The life of crime is the only one [Ben Affleck’s character] knows, and he is good at what he does, but there are broad hints — well, O.K., blazing neon signs — that his heart is no longer in it.”).

32

this case nor is there an allegation in this case that [assault weapons] were used; I

want to make sure you understand that.” Id. at 1307. The district court also

noted that in the film “the perpetrators of the crime had somebody outside the

house of some of the victims during the course of the crime; again, no such

allegation in this case, and you’ll hear no proof to that effect in this case.” Id.

The district court clarified that it had provided this second instruction “to make

sure there [was] no misunderstanding.” Id. As we have made clear, “[a]bsent

evidence to the contrary, we must presume that juries understand and abide by a

district court’s limiting instructions.” Downing, 297 F.3d at 59. There is no

evidence suggesting otherwise in this case.

This Court has in the past declined to second‐guess a district court’s

admission of relevant video or media evidence where the evidence bears an

identifiable connection to an issue or defendant in the case. See, e.g., United

States v. Cromitie, 727 F.3d 194, 225 (2d Cir. 2013) (finding that a district court was

“well within [its] discretion” in admitting into evidence a twenty‐second‐long

video of a demonstration explosion set off by a bomb that was “constructed with

the type and amount of material that the defendants thought was in the fake

devices they were planning to use in the operation”); Abu‐Jihaad, 630 F.3d at

33

131‐35 (affirming the district court’s admittance of various website materials —

including pro‐jihadist videos and Osama bin Laden’s 1996 fatwa against the

United States — on the theory that they were relevant to the understanding the

operations at issue in the case, despite the materials’ potential to inflame a juror’s

passions); United States v. Salameh, 152 F.3d 88, 111 (2d Cir. 1998) (per curiam)

(affirming the district court’s ruling to admit a videotape that “showed a man

driving a truck into a building that was flying an American flag” and then the

building exploding because “[t]he videotape . . . closely resembled the actual

events at the World Trade Center and provided further evidence of motive and

intent,” and the district court was within its discretion to find that this

“significant probative value . . . was not substantially outweighed by the danger

of unfair prejudice” — namely, ʺ[t]he sulphurous anti‐American sentiments

expressed in the terrorist materials[, which] no doubt threatened to prejudice the

jury against the defendants”). To that end, our rulings have been in line with

those of our sister circuits.21 We see no reason to depart from this precedent in

21 See, e.g., United States v. Schneider, 801 F.3d 186, 199‐200 (3d Cir. 2015) (affirming district court’s evidentiary ruling in prosecution for traveling in foreign commerce with intent to engage in sex with a minor to admit excerpts from the film, Nijinsky, which showed a famous ballet dancer and his older patron and lover, because the victim testified that the defendant had shown him the film); United States v. Smith, 749 F.3d 465, 495‐96 (6th Cir.) (holding that, in a trial on mail fraud charges arising from a scheme to

34

the circumstances here, where the movie clips in question had real probative

value and the potential for prejudice, we conclude, was slight.

* * *

In sum, the district court’s ruling to admit the movie clips from The Town

into evidence was not arbitrary and irrational. The clips were relevant to the

issues and defendants in the case and, importantly, they were short and

narrowly tailored. Further, the district court provided not one but two curative

instructions to minimize any potential for prejudice from the few differences

between the clips and the 2012 robbery. It made clear — if it was not clear

enough already — that the clips represented “Hollywood and not Brooklyn

federal court.” Joint App’x 1075. defraud investors, the district court did not err in admitting clips from the movie The Boiler Room that depicted salesmen deceiving potential investors, where former employees of the defendants’ company testified that the movie was provided to employees for training purposes), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 307 (2014), rehʹg denied, 135 S. Ct. 1034 (2015); United States v. Jayyousi, 657 F.3d 1085, 1108 (11th Cir. 2011) (affirming the district court’s ruling, in terrorism case, to admit a seven‐minute‐long portion of a 1997 CNN interview with Osama Bin Laden to which the alleged co‐conspirators had briefly referred in intercepted phone calls); United States v. Wills, 346 F.3d 476, 489, 497 (4th Cir. 2003) (affirming the district court’s ruling to admit clips from the movie Casino as relevant to help explain a reference the defendant made during a tape‐recorded conversation). But cf. United States v. Gamory, 635 F.3d 480, 493‐94 (11th Cir. 2011) (ruling that the district court abused its discretion in admitting into evidence a rap video in which the defendant appeared in light of its minimal probative value, that it contained inadmissible hearsay statements, and that “[t]he lyrics presented a substantial danger of unfair prejudice because they contained violence, profanity, sex, promiscuity, and misogyny,” but concluding that this was harmless error in any event).

35

Our courtrooms are not movie theaters. But we cannot assume that our

jurors — whom we routinely ask to pore over the violent and often grisly details

of real crimes — are such delicate consumers of media that they would so easily

have their passions aroused by short film clips of the sort at issue here. In this

case, the district court acted well within its discretion in permitting the jury to

see one minute and seven seconds of relevant Hollywood fiction during the

course of a four‐day criminal trial in real‐life Brooklyn federal district court.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments:

Find a Lawyer

Find a Case