Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 09-23-2020

Case Style:

Louise A. Gomez v. Tammy J. Smith

Case Number: C089338

Judge: Robie, J.

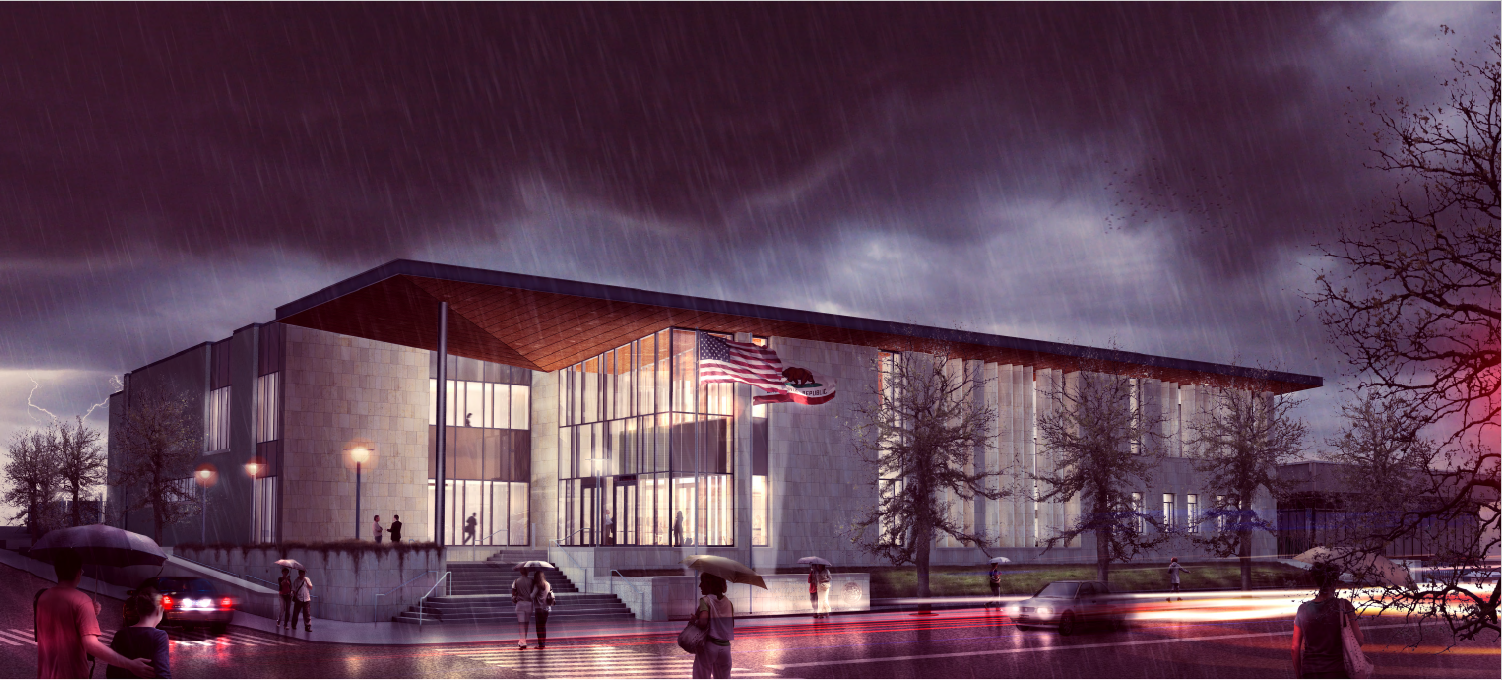

Court: California Court of Appeals Third Appellate District on appeal from the Superior Court, County of Shasta

Plaintiff's Attorney:

Redding, California Elder Law Lawyer DirectoryOR

Just Call 855-853-4800 for Free Help Finding a Lawyer Help You.

OR

Just Call 855-853-4800 for Free Help Finding a Lawyer Help You.

Defendant's Attorney:

Grass Valley, California Elder Law Lawyer DirectoryOR

Just Call 855-853-4800 for Free Help Finding a Lawyer Help You.

OR

Just Call 855-853-4800 for Free Help Finding a Lawyer Help You.

Description: Redding, CA - Elder Law Lawyer - Intentional interference with expected

inheritance, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and elder abuse.

Frank Gomez and plaintiff Louise Gomez rekindled their love late in life, over 60

years after Frank broke off their first engagement because he was leaving to serve in the

Korean War. Frank’s children from a prior marriage, defendants Tammy Smith and

Richard Gomez, did not approve of their marriage. After Frank fell ill, he attempted to

establish a new living trust with the intent to provide for Louise during her life. Frank’s

illness unfortunately progressed quickly. Frank’s attorney, Erik Aanestad, attempted to

have Frank sign the new living trust documents the day after Frank was sent home under

hospice care. Aanestad unfortunately never got the chance to speak with Frank because

Tammy and Richard intervened and precluded Aanestad from entering Frank’s home.

Frank, who was bedridden, died early the following morning.

Louise sued Tammy and Richard for intentional interference with expected

inheritance, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and elder abuse. Tammy filed a

cross-complaint against Louise for recovery of trust property. Following a court trial, the

trial court issued a statement of decision finding in favor of Louise as to her intentional

interference with expected inheritance cause of action and in favor of Tammy and

Richard as to the remaining causes of action. The trial court also ruled against Tammy

on her cross-complaint. Tammy appeals the judgment in favor of Louise; she does not

appeal the trial court’s ruling with regard to her cross-complaint. Richard did not file a

notice of appeal.

Tammy argues the judgment should be reversed because: (1) Louise admitted she

did not expect to receive an inheritance; (2) Tammy’s conduct was not tortious

independent of her interference; (3) the trial court applied an erroneous legal

1 Due to the commonality of the Smith and Gomez last names, we identify each

individual by his or her full name in the first instance and thereafter by his or her first

name only. No disrespect is intended.

3

standard in its capacity analysis; (4) there is no substantial evidence to support the finding

that Frank had the capacity to execute the trust documents; (5) the trial court’s finding

that Tammy knew Louise expected an inheritance is contradicted by the evidence; and

(6) alternatively, the constructive trust remedy is fatally ambiguous. We affirm.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

We discuss the trial testimony pertinent to the issues raised by Tammy here and

set forth the trial court’s findings in the statement of decision in the pertinent portions of

the discussion below.

As background, prior to Frank’s marriage to Louise, Frank was married to Beverly

Gomez. Frank and Beverly created the Frank and Beverly Gomez 1998 Revocable Trust.

Frank and Beverly had four children: Tammy, Richard, and two other daughters.

Beverly predeceased Frank in 2012.

I

Louise’s Case

A

Louise

Louise and Frank married in November 2014. In 2015, Frank had a stroke and

later had surgery to correct an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Prior to the surgery, Frank

went to see an attorney, Clarence McProud; Frank told Louise “he wanted to be sure that

[she] was okay and taken care of if anything happened to him.” Frank was admitted to

the hospital on July 14, 2016;2 he was later transferred to a nursing home.

Aanestad went to meet with Frank at the nursing home on August 15 to create a

new trust, the Frank Gomez and Louise Gomez living trust. Louise was present for part

of the conversation between Frank and Aanestad. Aanestad asked Frank “what he

2 All further date references are to 2016 unless otherwise specified.

4

wanted done and who were the beneficiaries going to be” and what percentages to assign

to each beneficiary. Louise explained Frank “wanted to fix [the percentages] so that

Ric[hard] would get more of a percentage.” She said “Ric[hard] actually would have

been the only one to benefit from the new trust.” Louise did not discuss the trust with

Frank after Aanestad left.

Frank went home under hospice care on August 19. That day, when Frank and

Louise were discussing the upcoming meeting with Aanestad, Frank said “[his] kids and

[Louise] w[ould] be taken care of” and Louise “could stay in the house as long as [she]

wanted.” Louise said Frank’s “body was weak” and he did not “rouse as fast as he

normally would” but “[h]is mind knew what was going on at every point.”

On August 20, Louise administered morphine to Frank around 8:00 a.m. and 9:00

a.m. but could not recall when she gave him another dose. Louise also called hospice to

request a suction machine because Frank had asked for one.

Frank and Louise discussed Aanestad’s expected arrival later that morning. A

little later, Tammy and Richard arrived at the house. Louise told Tammy, “[t]he lawyer’s

coming to see your dad, and you’re going to have to stay out while they’re talking

because they’ll want to be talking privately.” Tammy responded, “[d]on’t let him sign

anything” and “[y]ou have to promise me that you’ll not let him sign anything.” Louise

said, “I can’t promise, you know, you have to wait and see” and “[w]e don’t know what

will happen.”

When Aanestad arrived at the house, Louise was tending to Frank. Louise did not

see anything but she could hear Tammy yelling. Aanestad arrived around 11:30 a.m.,

someone called the sheriff’s office, and Aanestad left. After Aanestad left, Louise told

Frank that Aanestad had gone back to his office but she would call him to return. Frank

responded, “God be willing.” Louise also told Frank that his friend, Chuck Farmer, was

coming to visit him; Frank responded, “ ‘Chuck E. Cheese,’ ” which was his nickname

for Farmer. Farmer arrived shortly thereafter and he and Frank talked for a little while.

5

Frank passed away at 1:00 a.m. on August 21.

B

Kenneth Meyers

Kenneth Meyers was Frank’s financial advisor and one of his close friends.

Meyers attended the first meeting between Aanestad and Frank. Frank told Meyers he

wanted to leave a life estate for Louise and for his assets to transfer to his children upon

Louise’s death. Meyers and Frank spoke about it more than once and Frank’s expression

of intent remained the same in all of their conversations leading up to Frank’s passing.

One night after Frank started having problems keeping food down, Frank told

Meyers that Tammy had called and was quizzing him “about why he was going to go see

an attorney.” Frank told Tammy it was none of her business.

C

Aanestad

Aanestad first met Frank on August 15. When they spoke, Frank was lucid and

had all his capacities with him. Frank wanted a survivor’s trust; he wanted “[a]ll to

[Louise]” and then to his children upon her death.

On August 20, Aanestad and his paralegal arrived at Frank’s house between 11:00

a.m. and 11:30 a.m. with the purpose of having Frank and Louise sign the updated estate

planning documents. Richard, Tammy, and another gentleman confronted them before

they stepped off the street onto the driveway. “Tammy was saying, You’re not going in

the house. This isn’t her house. It’s my mom’s house.” Tammy further said “quote,

unquote, it wasn’t Frank’s decision to make and that was their mother’s house and that

Frank cannot change the trust.” Richard and Tammy prevented Aanestad and his

paralegal from entering the house. Aanestad’s paralegal called Meyers, who said they

“should just desist and go.” After the sheriff arrived, Aanestad and his paralegal left.

Frank did not review the new trust documents between August 15 and 20.

6

On cross-examination, Aanestad was asked how long it would take a healthy client

to review and sign over a hundred pages of estate planning documents. Aanestad

estimated it would generally take between one and four hours. On recross-examination,

after a portion of his deposition testimony was read, Aanestad confirmed he could not

recall whether Tammy said anything about a trust during their altercation.

D

Judith Piffero

Judith Piffero is Louise’s daughter. Piffero spoke with Frank on August 20 and

was there when Tammy blocked Aanestad from entering the front door. Piffero helped

change Frank after he lost his bowels and vomited, which occurred approximately an

hour or two after the Aanestad incident. As Piffero and others were rolling Frank around

to change him, Frank said his back was hurting.

E

Helen Crawford

Helen Crawford is a psychiatrist and was recognized by the court as an expert in

psychiatry. Crawford reviewed Frank’s medical records and stated her opinion that,

based on those records, Frank would have been able to make financial decisions on

August 17 and there were indicators he was able to make financial decisions on

August 19. As to the morphine Frank received, Crawford did not expect the medication

to impact his decision-making ability. Although the medication affects people differently

and may make a person more or less responsive, there was nothing in the record

indicating Frank failed to retain the capacity to review a complex trust document because

of the pain medication he had received.

The only abnormality in the records was Frank’s inability to recall the correct

year. That, “by itself, [was] not enough for [Crawford] to believe that you would say

somebody doesn’t have capacity to participate in making decisions.” Crawford noted the

record did not contain much information relating to Frank’s capacity after his discharge

7

from the nursing home. The records showed, however, that Frank requested a suction

machine on August 20, indicating he was aware of his needs and could ask for assistance.

Crawford understood the record she relied upon indicated Louise made the call to hospice

and told them Frank was requesting a suction machine; Frank did not make the call.

F

Christopher Gomez-Smith

Christopher Gomez-Smith is Tammy’s son. He went to see Frank on August 20;

he arrived at the house around 12:45 p.m. or 1:00 p.m. When Christopher arrived at the

house, there was a sheriff’s car out front. Christopher asked his mother, father, and uncle

what happened prior to his arrival. His father said an attorney was there to change a will.

II

Tammy’s Case

A

Tammy

In 2015, Frank told Tammy he wanted to execute a third amendment to the Frank

and Beverly Gomez 1998 Revocable Trust to give Louise a life estate in his house. Frank

asked Tammy for her thoughts. Frank intended for Tammy and her husband, Tim Smith,

to take care of the maintenance on the house. Tammy told Frank she did not agree with

his decision and did not want to be linked to Louise. Frank executed the third

amendment to the Frank and Beverly Gomez 1998 Revocable Trust in July 2015.

Tammy visited Frank on August 19. Frank could barely whisper hello in the

morning and was minimally responsive around 3:00 p.m. that afternoon. Tammy

returned to the house the next morning around 9:00 a.m. or 9:30 a.m. Louise told her,

“there’s a lawyer coming.” Tammy thought to herself, “I gotta see what Dad looks like

because this doesn’t seem right.” Tammy went to see Frank; he did not respond when

she greeted him.

8

Tammy asked Louise to call the attorney and cancel the appointment. Louise

refused. Tammy also asked about the subject matter of the attorney’s visit; Louise said it

was none of Tammy’s business. Louise told Tammy: “Well, we’re still gonna like go

through it. We’ll -- if need be, they would take his hand -- SHE would take his hand and

sign with an ‘X.’ ”

When the attorney and paralegal arrived, Tammy told them to leave, it was not a

good time, and Frank was “in no condition.” They ignored her. Tim was talking too but

Tammy could not recall what he said. When Tammy reiterated it was not a good time,

the attorney responded, “Well, we’ll determine that.” The attorney continued: “We’ll

take an ‘X,’ and we’ll sign it.” Piffero opened the screen door twice to let the attorney in,

but Tammy closed it. Tammy asked someone to call the sheriff. Tammy then went

inside and picked up the phone, which was ringing. Meyers was on the other end of the

line. Meyers told Tammy to let the attorney in, “[t]his is what your dad would want.”

Tammy said no and ultimately hung up on Meyers. Shortly thereafter, Tim told Tammy

the sheriff was there and “they’re already leaving.” Tammy said okay and went into the

family room. Tammy never got a response or utterance from Frank on August 20; she

tried to talk to him and prayed over him throughout the day.

Tammy acknowledged that, in July 2014, she researched “what Louise did with

[Louise’s] Santa Cruz house.” She denied ever telling Aanestad, “ ‘This is my mother’s

house.’ ”

B

Michelle Tagg

Michelle Tagg is a medical social worker at Hospice of the Foothills. Tagg

performs the initial intakes with patients for admission. As part of the intake procedure,

Tagg performs a basic mental health assessment and determines whether a patient is

responsive.

9

Tagg assessed Frank at home on August 19. She was there late morning or early

afternoon and stayed for 45 minutes to an hour. Frank was minimally responsive but

engaged. “He was groggy, drowsy, but he was not disoriented. He was not hallucinating.

He was not delusional. He knew where he was. He was speaking clearly about events

that [Louise] had corroborated the information [sic].”

C

Gerry Tribble

Gerry Tribble is a registered nurse at Hospice of the Foothills. She had no

independent recollection of meeting with Frank on August 19; she relied exclusively on

her notes. Tribble acknowledged her notes were in conflict regarding whether Frank was

oriented and able to answer questions during her assessment.

DISCUSSION

The tort of intentional interference with expected inheritance was first recognized

in California in 2012. (Beckwith v. Dahl (2012) 205 Cal.App.4th 1039, 1050-1056.) To

establish a defendant committed the tort, a plaintiff must prove six elements. “First, the

plaintiff must p[rove] he [or she] had an expectancy of an inheritance. It is not necessary

to [prove] that ‘one is in fact named as a beneficiary in the will or that one has been

devised the particular property at issue. [Citation.] That requirement would defeat the

purpose of an expectancy claim. . . . It is only the expectation that one will receive some

interest that gives rise to a cause of action. [Citations.]’ [Citation.] Second, as in other

interference torts, the [plaintiff] must [prove] causation. ‘This means that, as in other

cases involving recovery for loss of expectancies . . . there must be proof amounting to a

reasonable degree of certainty that the bequest or devise would have been in effect at the

time of the death of the testator . . . if there had been no such interference.’ [Citation.]

Third, the plaintiff must p[rove] intent, i.e., that the defendant had knowledge of the

plaintiff’s expectancy of inheritance and took deliberate action to interfere with it.

[Citation.] Fourth, the [plaintiff] must [prove] that the interference was conducted by

10

independently tortious means, i.e., the underlying conduct must be wrong for some

reason other than the fact of the interference. [Citation.] Fi[fth], the plaintiff must

p[rove] he [or she] was damaged by the defendant’s interference. [Citation.] [¶] [And,

sixth], [the] defendant must direct the independently tortious conduct at someone other

than the plaintiff.” (Id. at p. 1057.)

I

Standard Of Review

The parties dispute the appropriate standard of review on appeal pertaining to

Tammy’s various arguments. Where the facts are undisputed, the effect or legal

significance of those facts is a question of law. (Ghirardo v. Antonioli (1994) 8 Cal.4th

791, 799.) We review any questions of law de novo. (Id. at p. 801.)

We review findings of fact for substantial evidence. “ ‘In general, in reviewing a

judgment based upon a statement of decision following a bench trial, “any conflict in the

evidence or reasonable inferences to be drawn from the facts will be resolved in support

of the determination of the trial court decision. [Citations.]” [Citation.] In a substantial

evidence challenge to a judgment, the appellate court will “consider all of the evidence in

the light most favorable to the prevailing party, giving it the benefit of every reasonable

inference, and resolving conflicts in support of the [findings]. [Citations.]”

[Citation.] We may not reweigh the evidence and are bound by the trial court’s

credibility determinations. [Citations.] Moreover, findings of fact are liberally construed

to support the judgment.’ [Citation.]

“ ‘The substantial evidence standard applies to both express and implied findings

of fact made by the superior court in its statement of decision rendered after a nonjury

trial.’ [Citation.] ‘The court’s statement of decision is sufficient if it fairly discloses the

court’s determination as to the ultimate facts and material issues in the case.’ [Citation.]

‘ “Where [a] statement of decision sets forth the factual and legal basis for the decision,

any conflict in the evidence or reasonable inferences to be drawn from the facts will be

11

resolved in support of the determination of the trial court decision.” ’ ” (In re Marriage

of Ciprari (2019) 32 Cal.App.5th 83, 93-94.)

II

Substantial Evidence Supports The Finding Louise Expected An Inheritance

The trial court found Louise expected an inheritance, relying in substantial part on

the testimony of Aanestad, a witness the court found credible and unbiased. The court

explained: “Mr. Aanestad testified that the decedent wanted to change his existing trust

(Frank and Beverly Gomez Trust) to [the] Frank and Louise Gomez Trust. He further

testified that the decedent made it clear to him that he wanted plaintiff to be the trustee

and have a life estate in the trust assets which would pass to the decedent’s children upon

plaintiff’s death.” The court explained Louise testified she was present during the August

15 meeting between Aanestad and Frank, and she “understood decedent’s wishes were to

create a new trust, the Frank and Louise Gomez Living Trust.” The court further

explained Louise “understood that the decedent’s intention with regard to the trust was

that she be taken care of during her lifetime.”

Tammy does not challenge the evidence cited by the trial court as being

unsupported in the record. Tammy instead argues two other sections of Louise’s trial

testimony negated the expectancy of an inheritance element and constituted “the only

substantial evidence on the precise point of Louise’s expectancy of an inheritance under

the 2016 version of the trust.” Louise disagrees with Tammy’s interpretation of Louise’s

testimony and asserts the evidence cited by the trial court supports its finding. We agree

with Louise.

In the first section of testimony upon which Tammy relies, Louise was asked

whether she recalled what Frank and Aanestad discussed “in regards to who was going to

receive what from the trust.” Louise responded: “Yes. He had changed the percentages

on the kids, and he brought -- he wanted to fix it so that Ric[hard] would get more of a

percentage. Ric[hard] actually would have been the only one to benefit from the new

12

trust.” Tammy asserts this testimony constitutes an admission that Louise did not expect

to inherit anything from the 2016 trust because Louise believed the trust would only

benefit Richard. We disagree. Louise’s testimony must be read in context, considering

the immediately preceding exchange:

“Q. And do you recall what kind of questions Erik was asking Frank?

“A. He wanted to know what he wanted done and who were the beneficiaries

going to be. And the percentages. Because he was going to change them.

“Q. Did Frank have a habit of messing with the percentages of this trust, to your

knowledge?

“A. He did. Apparently when he was mad at somebody or one of the kids irked

him in some way, well, their percentage might have gone down.

“Q. So this is something that was a running theme with Frank about --

“A. Yeah.

“Q. -- if he was happy with somebody, the percentage would go up, in his mind.

And if he was upset with somebody, the percentage would go down?

“A. Yeah. Yeah. It didn’t happen often, but there were a couple times that he

made amendments.

“Q. Right. Did he ever just like when they left the room, say something

jokingly?

“A. I don’t know.

“Q. Okay. No, that’s fine. Do you recall what Erik -- or what Frank said in

regards to who was going to receive what from the trust?

“A. Yes. He had changed the percentages on the kids, and he brought -- he

wanted to fix it so that Ric[hard] would get more of a percentage. Ric[hard] actually

would have been the only one to benefit from the new trust.”

Reading this exchange in context and accepting as true all inferences that might

reasonably be drawn in favor of the judgment (In re Marriage of Ciprari, supra, 32

13

Cal.App.5th at p. 94), we find no affirmative admission by Louise that she did not expect

to receive an inheritance under the new trust. It is reasonable to infer Louise answered

the question in the context of the beneficiary percentages allocated to Frank’s children. It

is further clear from Louise’s later testimony that she was aware the trust to be created by

Aanestad was the “Frank Gomez and Louise Gomez living trust.” To the extent there

was a factual conflict in the evidence, we assume the trial court resolved the conflict in

favor of Louise. (Church of Merciful Saviour v. Volunteers of America, Inc. (1960) 184

Cal.App.2d 851, 856.)

In the second section of testimony upon which Tammy relies, Louise was asked

whether, by 2015, Frank had spoken to Louise about his trust. Louise said he had not

said much to her about it except that he had to make some changes and that is why he

contacted Aanestad. Louise was then asked whether, after Aanestad left on August 15,

she recalled any conversation with Frank about the trust. Louise responded, no. Tammy

fails to explain, and we fail to see, how this testimony supports her argument. The

testimony has no bearing on whether Louise expected to receive an inheritance on

August 20.

The evidence cited by the trial court, which Tammy does not challenge, constitutes

substantial evidence supporting the trial court’s finding.

III

Substantial Evidence Supports The Finding Tammy Knew Of Louise’s Expectation

The trial court found Tammy knew of Louise’s expectation of inheritance when

she blocked Aanestad from entering the home. The court found Tammy was unhappy

about Frank’s marriage to Louise. The court further explained: “Witness Kenneth Myers

[sic] testified that the decedent had informed him that defendant Tammy Smith was

prying into his business and questioning him about why he was meeting with an attorney.

Decedent expressed his anger at his daughter (Ms. Smith) for interfering. [Citation.] Mr.

Myers [sic] also testified that when Mr. Aanestad arrived at the decedent’s home on

14

August 20, 2016, Ms. Smith called Mr. Myers [sic] screaming profanities.” “Defendants’

actions and comments directed at Mr. Aanestad when he arrived at the decedent[’s] and

plaintiff’s home on August 20, 2016 are also circumstantial evidence that defendants

knew the purpose of Mr. Aanestad’s visit was to create a trust wherein plaintiff would

receive an inheritance. Mr. Aanestad testified that as soon as he stepped out of his car, he

was confronted by the defendants. He described Ms. Smith as confrontational and

screaming that he could not enter the house because it was her mother’s home. Mr.

Aanestad testified that Ms. Smith stated, ‘It wasn’t Frank’s decision to make and that was

their mother’s house and that Frank cannot change the trust.’ The defendants then

physically blocked the doorway refusing to allow Mr. Aanestad to enter the decedent[’s]

and plaintiff’s home. Mr. Aanestad testified he was prevented from entering the

residence by the defendants’ actions.”

Tammy argues the trial court’s finding that she knew of Louise’s inheritance

expectation is contradicted by the evidence. As to Aanestad’s testimony quoted by the

trial court, Tammy argues the trial court failed to account for or credit Aanestad’s

testimony on recross-examination that he could not recall Tammy “ ‘say[ing] anything

about any trust.’ ” Tammy further argues the portions of Meyers’ testimony noted by the

trial court were “remote pieces of evidence” failing to “provide any actual proof that

Tammy had knowledge of a 2016 version of a trust being drafted, especially in light of

the fact that the 2016 trust was drafted starting August 15th or 16th, 2016” and the

evidence did not “logically tend to prove that Tammy had any knowledge of an

expectancy in favor of Louise.”

We note the trial court’s quotation of Aanestad’s testimony -- i.e., that Tammy

said, “It wasn’t Frank’s decision to make and that was their mother’s house and that

Frank cannot change the trust” -- was included in the tentative statement of decision as

support for the trial court’s finding that Tammy had knowledge of Louise’s expectancy.

Although Tammy objected to the trial court’s reliance on Meyers’ testimony in her

15

objections to the tentative statement of decision, Tammy did not challenge the trial

court’s reliance on this portion of Aanestad’s testimony, as she does on appeal.

We conclude Tammy has forfeited the claim of factual error in the statement of

decision with regard to Aanestad’s testimony for purposes of appeal. (See Golden Eagle

Ins. Co. v. Foremost Ins. Co. (1993) 20 Cal.App.4th 1372, 1380 [a party forfeits any

defects in the statement of decision by failing to file timely objections].) “Code of Civil

Procedure section 634 and California Rules of Court, rule 232, taken together, clearly

contemplate any defects in the trial court’s statement of decision must be brought to the

court’s attention through specific objections to the statement itself . . . . By filing specific

objections to the court’s statement of decision a party pinpoints alleged deficiencies in

the statement and allows the court to focus on the facts or issues the party contends were

not resolved or whose resolution is ambiguous.” (Golden Eagle Ins. Co., at p. 1380.)

Our Supreme Court has explained that “it would be unfair to allow counsel to lull the trial

court and opposing counsel into believing the statement of decision was acceptable, and

thereafter to take advantage of an error on appeal although it could have been corrected at

trial. . . . It is clearly unproductive to deprive a trial court of the opportunity to correct

such a purported defect by allowing a litigant to raise the claimed error for the first time

on appeal.” (In re Marriage of Arceneaux (1990) 51 Cal.3d 1130, 1138.)

We need not address Tammy’s argument that Meyers’ testimony, by itself, failed

to prove Tammy knew of Louise’s expectation. We resolve any conflict in the evidence

in support of the trial court’s determination and give the evidence most favorable to

Louise the benefit of every reasonable inference. (In re Marriage of Ciprari, supra, 32

Cal.App.5th at p. 94.) It may reasonably and logically be inferred from the following

evidence that Tammy knew the purpose of Aanestad’s visit on August 20 was to have

Frank sign a new trust document and that Louise expected to receive an inheritance:

(1) Frank had previously told Tammy, when he discussed the third amendment to the

Frank and Louise Gomez 1998 Revocable Trust, that he intended to provide a life estate

16

in the house for Louise; (2) Tammy told Aanestad, “[i]t wasn’t Frank’s decision to make”

because “that was their mother’s house”; (3) when Louise told Tammy an attorney was

coming to meet with Frank, Tammy responded, “You have to promise me that you’ll not

let him sign anything”; (4) Meyers testified Frank told him Tammy was questioning

Frank why he was meeting with an attorney; (5) Tim, Tammy’s husband, told their son

the attorney was there to change the will; and (6) Tammy researched what Louise had

done with Louise’s house in Santa Cruz in 2014, indicating Tammy was interested in

Louise’s assets.

We conclude the trial court’s finding was supported by substantial evidence.

IV

The Trial Court Did Not Err In Finding

Tammy Had Directed Tortious Conduct Toward Frank

The trial court identified two types of tortious conduct directed by Tammy toward

Frank. The first was undue influence; the second was breach of fiduciary duty. Tammy

challenges both findings.

A

The Requisite Element Of Tortious Conduct

The tort of intentional interference with expected inheritance “is outlined in

section 774B of the Restatement Second of Torts,” which provides, “ ‘[o]ne who by

fraud, duress or other tortious means intentionally prevents another from receiving from a

third person an inheritance or gift that he [or she] would otherwise have received is

subject to liability to the other for loss of the inheritance or gift.’ ” (Beckwith v. Dahl,

supra, 205 Cal.App.4th at p. 1050.) This liability “is limited to cases in which the actor

has interfered with the inheritance or gift by means that are independently tortious in

character. The usual case is that in which the third person has been induced to make or

not to make a bequest or a gift by fraud, duress, defamation or tortious abuse of fiduciary

duty, or has forged, altered or suppressed a will or a document making a gift. In the

17

absence of conduct independently tortious, the cases to date have not imposed liability

under the rule stated in this Section. Thus one who by legitimate means merely

persuades a person to disinherit a child and to leave the estate to the persuader instead is

not liable to the child.” (Rest.2d Torts, § 774B, com. c, pp. 58-59.) In other words,

liability arises if the interference resulting in injury is wrongful by some measure beyond

the fact of the interference itself, such as improper motives or the use of improper means.

B

Substantial Evidence Supports The Undue Influence Finding

The trial court’s undue influence analysis was comprised of the following:

“Defendant Tammy Smith admitted at the time of trial that prior to her father’s death she

had researched online regarding plaintiff’s ownership in plaintiff’s own separate property

in Santa Cruz, California demonstrating her overzealous interest in her father[’s] and his

new wife’s properties. [¶] Defendant Tammy Smith then actively interfered with her

father’s decision to change his will as evidenced by the decedent’s comments to Kenneth

Myers [sic] who described decedent as irritated and agitated by Ms. Smith’s interference.

At the time of Ms. Smith exerting this pressure on the decedent, Kenneth Myers [sic]

testified that the decedent was in poor physical health and having difficulty keeping food

down. These facts demonstrate that the decedent was clearly under distress.” The court

continued: “In this case, defendants’ actions on August 20, 2016 (and in the days/weeks

leading up thereto) constituted undue influence where the evidence was that although

decedent was oriented and mentally competent, he was physically bedridden and under

distress due to his medical condition. Defendants’ [sic] knew of the decedent’s physical

weakness and distress and took actions whereby they physically separated decedent’s

attorney from decedent intentionally preventing decedent from confirming an estate plan

that he had been trying to put in place for months.”

Tammy argues the trial court relied on two pieces of evidence to support its

finding that she exerted undue influence over Frank: (1) Tammy’s research regarding the

18

ownership of Louise’s Santa Cruz home in 2014; and (2) Frank’s discussion with Meyers

one to two months prior to Frank’s death, during which Frank said he was irritated by

Tammy’s interference in his business. Tammy argues neither piece of evidence supports

a finding of undue influence because the events occurred well prior to August 20 and her

research regarding Louise’s house was not directed at Frank.

We do not view the two pieces of evidence discussed by the trial court in isolation

to determine whether each incident by itself supports a finding of undue influence, as

Tammy proposes. We consider whether from the totality of the facts and circumstances,

the trial court’s finding of undue influence is supported by substantial evidence.

“Undue influence consists: [¶] 1. In the use, by one in whom a confidence is

reposed by another, or who holds a real or apparent authority over him [or her], of such

confidence or authority for the purpose of obtaining an unfair advantage over him [or

her]; [¶] 2. In taking an unfair advantage of another’s weakness of mind; or, [¶] 3. In

taking a grossly oppressive and unfair advantage of another’s necessities or distress.”

(Civ. Code, § 1575.) The trial court’s finding of undue influence is supported by

substantial evidence that Tammy took a grossly unfair advantage of Frank’s distress.

Tammy indisputably “knew of [Frank’s] physical weakness and distress and took actions

whereby [she] physically separated [his] attorney from [him] intentionally preventing

[Frank] from confirming an estate plan that he had been trying to put in place for

months.” Frank’s will was overborne by Tammy because he was bedridden and unable

to intervene when Tammy precluded Aanestad from entering the home. Tammy

precluded Frank from signing the new trust documents, an act the trial court found he

would have done if left to act freely.

We conclude substantial evidence supports the trial court’s finding that Tammy

exerted undue influence over Frank. Such conduct is wrongful beyond the fact of the

interference itself.

19

C

The Trial Court Did Not Err In Finding Tammy Breached Her Fiduciary Duty To Frank

The trial court’s breach of fiduciary duty analysis was comprised of the following:

“Defendant Smith argues that her actions are authorized under the law as she was acting

under a durable power of attorney. [Citation.] Defendant Smith has not cited any legal

authority in support of this argument. [¶] The Court does not find that defendant Smith

acted lawfully under the power of attorney, in fact, the Court finds defendant Smith’s

action[s] constitute tortious conduct in breach of her fiduciary duty to the decedent.” The

court found: “Frank Gomez, the decedent, was the grantor of the trust. As the grantor,

he retained all incidents of ownership and control over the trust assets. He retained the

right to amend or revoke the trust instrument at any time prior to his death. [¶]

Defendant Tammy Smith had a fiduciary obligation to decedent Frank Gomez and was

prohibited by law from placing her own interests before those of the decedent as it related

to acting as his power of attorney.

“The evidence is undisputed that Frank Gomez had attempted to contact his prior

probate attorney, McProud, for months prior to his death in order to change his trust and

create a new trust, creating a life estate for plaintiff. It is undisputed that decedent was

mentally competent when he attempted to make contact with McProud and confided to

two of his closest friends . . . that he wished to change his trust to leave a life estate for

plaintiff. It is also evident that decedent was competent when he met with Mr. Aanestad

on August 15, 2016.

“Despite decedent making his wishes clear, Ms. Smith exerted undue pressure on

him and physically prohibited the decedent from being able to execute the final trust

documents, an action which not only deprived the decedent of finalizing his own wishes

with regard to distribution of his property, but Ms. Smith’s actions operated to benefit her

own interests as she was the primary beneficiary under the trust the decedent wished to

extinguish by creating the new trust.”

20

Tammy argues the trial court erred in its breach of fiduciary duty analysis for two

reasons: (1) “it focuse[d] on the fact of the interference, using it as the basis for finding

the conduct wrongful,” whereas the pertinent element requires “ ‘the underlying conduct

must be wrong for some reason other than the fact of the interference’ ”; and (2) “Frank

clearly did give Tammy informed consent to act on his behalf, in advance, in very

specific written form when he signed the non-springing power of attorney in 1995 . . .

and, even more specifically, as to informed consent and specifically, ratification, . . . .”

Tammy believes she acted within her authority as Frank’s power of attorney because she

“was free to substitute her judgment for her father’s.” Louise does not address this

argument.

Frank executed a durable power of attorney in December 1995. The document

provides that Tammy, as Frank’s power of attorney, may “[g]enerally . . . do, execute,

and perform any other act, deed, matter, or thing, that in the opinion of the agent ought to

be done, executed, or performed in conjunction with this power of attorney, of every kind

and nature, as fully and effectively as the principal could do if personally present. The

enumeration of specific items, acts, rights, or powers in this instrument does not limit or

restrict, and is not to be construed or interpreted as limiting or restricting, the general

powers granted to the agent except where powers are expressly restricted.” It further

provides: “The principal hereby ratifies and confirms all that the agent shall do, or cause

to be done, by virtue of this power of attorney.”

Tammy acknowledges no case law supports her statement that “her actions were

authorized under the power of attorney, and thus could not be actionable.” She asserts,

however, that “[s]imple logic would dictate that if a person is acting within the scope of

their [sic] authority under a power of attorney, and taking action that is quite clearly

ratified by the principal, that this cannot be a wrongful act toward the principal.”

Essentially, Tammy asserts she cannot be held liable for breaching her fiduciary duty to

Frank because Frank gave her broad authority to act on his behalf and the power of

21

attorney provides that Frank ratified her conduct. This assertion traverses the line of

reason into absurdity.

An attorney-in-fact under a power of attorney is a fiduciary and thus owes

fiduciary duties to his or her principal. (Prob. Code, § 39.) Probate Code3

section 4266

provides: “The grant of authority to an attorney-in-fact, whether by the power of

attorney, by statute, or by the court, does not in itself require or permit the exercise of the

power. The exercise of authority by an attorney-in-fact is subject to the attorney-in-fact’s

fiduciary duties.” One such fiduciary duty is laid down in section 4232, subdivision (a):

“An attorney-in-fact has a duty to act solely in the interest of the principal and to avoid

conflicts of interest.” It is further well-established common law that an agent is dutybound to give the principal his or her undivided allegiance and to exercise toward the

principal the utmost good faith and loyalty. (Beeler v. West American Finance Co.

(1962) 201 Cal.App.2d 702, 705.)

The power of attorney signed by Frank did not authorize Tammy to act in

contravention of her fiduciary duties to him. Tammy was not “free to substitute her

judgment for her father’s” where her judgment was in direct contravention of Frank’s

wishes and born out of Tammy’s self-interest.

We also disagree with Tammy’s assertion that the trial court merely used the fact

of the interference as the basis for finding the conduct wrongful. The trial court found

the interference tortious because Tammy breached her fiduciary duty to Frank by

precluding him from meeting with his attorney to finalize his wishes regarding the

distribution of his property, when Tammy acted in her own self-interest. This finding

meets the independently tortious means requirement, which is satisfied “ ‘when

interference resulting in injury to another is wrongful by some measure beyond the fact of

3 All further statutory references are to the Probate Code unless otherwise specified.

22

the interference itself. Defendant’s liability may arise from improper motives or from the

use of improper means. They may be wrongful by reason of a statute or other regulation,

or a recognized rule of common law.’ ” (Allen v. Hall (1999) 328 Ore. 276, 285 [974

P.2d 199, 204].)

We find no basis to reverse the trial court’s finding that Tammy breached her

fiduciary duty of loyalty to Frank.

V

Tammy Failed To Prove Frank Did Not Have Mental Capacity

The trial court found Frank “was mentally competent and had capacity to make

legal decisions and perform legal acts on [August] 19 and 20, 2016 and that [Frank] had

the ability to appreciate the consequences of the particular act he wished to undertake

which was to finalize the trust plan that he had previously reviewed with Mr. Aanestad.”

(Bolding omitted; citing Lintz v. Lintz (2014) 222 Cal.App.4th 1346, 1352.) The trial

court found Tammy’s incapacity argument to be inconsistent with the evidence produced

at trial. The trial court addressed five pieces of evidence.

One: The trial court found Tagg’s testimony credible on the issue of capacity.

“Michelle Tagg a hospice social worker who cared for the decedent on August 19, 2016

testified that decedent was lethargic but he was engaged. [Citation.] She further

testified, ‘He was groggy, drowsy, but he was not disoriented. He was not hallucinating.

He was not delusional. He knew where he was. He was speaking clearly about events

that [Louise] had corroborated the information [sic].’ [Citation.] Ms. Tagg cared for the

decedent approximately nineteen hours prior to the arrival of Mr. Aanestad.”

Two: The trial court did not find credible or rely on Tribble’s testimony “due to

her conflicting notes and lack of personal recollection.”

Three: The trial court found credible Crawford’s “expert medical opinion that

decedent was mentally competent on August 19, 2016,” and her testimony “that there are

not many notations on the August 20, 2016 records but that the records do indicate that

23

the decedent was aware of his needs and requested assistance in response to those needs.”

The trial court explained that “[t]he nursing notations relied upon by Dr. Crawford were

also consistent with the testimony of plaintiff and witness Judith Piffero that the decedent

was aware and able to request assistance on August 20, 2016.”

Four: The trial court found Tammy’s expert, Patricia Bay, “unpersuasive on the

issue of mental capacity.”4

Five: The trial court found “defendant’s own text messages [were] indicative that

the decedent was mentally competent and aware of his surroundings and capable of

understanding and participating in communications. On August 19, 2016 at 5:18 p.m.

defendant Gomez texted defendant Smith that he was making arrangements for their

sister, Kathy, to say her ‘good byes’ to the decedent by phone. Defendant Gomez

specifically informs defendant Smith, ‘PLEASE don’t say anything to Dad or [Louise].

I’ll decide when.’ To which defendant Smith replies, ‘Maybe, I can do it with Mar.’

(referring to another sibling). If defendants were of the opinion that decedent was

unresponsive and mentally incapacitated, they would not have been concerned about

whether or when this information was conveyed to the decedent.”

Tammy challenges the trial court’s mental capacity analysis on two grounds. She

asserts: (1) the trial court applied an erroneous legal standard; and (2) the evidence was

insufficient to support a finding of capacity. Louise responds Tammy had the burden of

proving Frank did not have mental capacity on August 20, the trial court cited the correct

legal standard, and the evidence supported the trial court’s determination. We conclude

the trial court did not err.

4 We do not summarize Bay’s testimony because Tammy does not challenge this

finding.

24

A

The Trial Court Applied The Correct Legal Standard

Tammy argues the trial court applied the incorrect legal standard regarding mental

capacity because the trial court failed to “undertake the analysis called for under Probate

Code Section 812” and mistakenly relied on section 6100.5 when Lintz “specifically

holds that Probate Code Section 6100.5 is an inappropriate standard for assessing mental

capacity related to a trust, or trust amendment that is more complex than one analogous to

a simple will or codicil.” (Citing Lintz v. Lintz, supra, 222 Cal.App.4th at p. 1346.)

Louise disagrees, noting the trial court expressly referenced the correct standards under

sections 810 through 812.

Sections 810 to 812 set forth the mental capacity standard related to certain legal

acts and decisions. Section 810 establishes a rebuttable presumption “that all persons

have the capacity to make decisions and to be responsible for their acts or decisions,”

recognizing that persons with mental or physical disorders “may still be capable of

contracting, conveying, marrying, making medical decisions, executing wills or trusts,

and performing other actions.” (§ 810, subds. (a), (b).) Section 811, subdivision (a),

provides that a person lacks capacity when there is a deficit in at least one of the listed

mental functions and “a correlation [exists] between the deficit or deficits and the

decision or acts in question . . . .” The statute organizes the mental functions into four

categories: (1) alertness and attention (§ 811, subd. (a)(1)); (2) information processing

(§ 811, subd. (a)(2)); (3) thought processes (§ 811, subd. (a)(3)); and (4) ability to

modulate mood and affect (§ 811, subd. (a)(4)). A deficit in one of the listed mental

functions “may be considered only if the deficit, by itself or in combination with one or

more other mental function deficits, significantly impairs the person’s ability to

understand and appreciate the consequences of his or her actions with regard to the type

of act or decision in question.” (§ 811, subd. (b).)

25

Section 812 provides: “Except where otherwise provided by law, including, but

not limited to, . . . the statutory and decisional law of testamentary capacity, a person

lacks the capacity to make a decision unless the person has the ability to communicate

verbally, or by any other means, the decision, and to understand and appreciate, to the

extent relevant all of the following: [¶] (a) The rights, duties, and responsibilities created

by, or affected by the decision[;] [¶] (b) The probable consequences for the

decisionmaker and, where appropriate, the persons affected by the decision[; and] [¶]

(c) The significant risks, benefits, and reasonable alternatives involved in the decision.”

Tammy is correct that the testamentary capacity standards set forth in sections 810

through 812 apply to the new trust Frank wanted to execute on August 20 because the

trust was “unquestionably more complex than a will or codicil.” (Lintz v. Lintz, supra,

222 Cal.App.4th at pp. 1351-1353.) We do not agree, however, that the trial court

applied the incorrect standard. The trial court set forth the requirements under

sections 810 through 812. More importantly, the trial court applied those standards.

The finding that Frank “had the ability to appreciate the consequences of the

particular act he wished to undertake which was to finalize the trust plan that he had

previously reviewed with Mr. Aanestad” (bolding omitted) tracks the appreciation of

consequences standard pertinent to mental capacity, as outlined in section 811,

subdivision (b), and section 812, subdivision (b). The trial court further expressly

discussed testimony that Frank was lethargic, groggy, and drowsy, but engaged, not

disoriented, not hallucinating, and not delusional -- evidence pertinent to the enumerated

mental functions of alertness and attention and thought processes set forth in section 811,

subdivision (a)(1) and (3). The trial court also discussed evidence that Frank was aware

of his surroundings, capable of understanding and participating in communications,

aware of his needs, and able to request assistance -- evidence pertinent to Frank’s ability

to communicate under section 812 and the information processing mental functions listed

in section 811, subdivision (a)(2).

26

From the foregoing, we conclude the trial court applied the correct legal standard

under sections 810 through 812.

B

Tammy Had The Burden Of Proof

The parties quibble over who had the burden of proving Frank’s mental capacity

or incapacity at trial. Louise asserts Tammy had the burden of proving Frank’s

incapacity by clear and convincing evidence (citing Doolittle v. Exchange Bank (2015)

241 Cal.App.4th 529) because a rebuttable presumption exists under section 810,

subdivision (a), that all persons have the capacity to make testamentary decisions.

Tammy disagrees and asserts Doolittle does not support Louise’s argument. Tammy

believes Louise had the burden of proving Frank was mentally competent on August 20

because, to succeed on her cause of action, Louise had to prove “ ‘there was a reasonable

certainty that [she] would have received the inheritance if [Tammy] had not interfered’ ”

with the execution of the new trust documents. (Citing CACI No. 2205 (2017 ed.).)

Tammy further argues Louise’s reliance on the rebuttable presumption of capacity stated

in section 810 is misplaced because “the case at bar does not present as a trust contest,

but rather an [intentional interference with expected inheritance] tort claim.”

Tammy is correct insofar as Louise had the burden of proving causation to

succeed on her cause of action. (Beckwith v. Dahl, supra, 205 Cal.App.4th at p. 1057.)

“ ‘This means that, as in other cases involving recovery for loss of expectancies . . . there

must be proof amounting to a reasonable degree of certainty that the bequest or devise

would have been in effect at the time of the death of the testator . . . if there had been no

such interference.’ ” (Ibid., citing Rest.2d Torts, § 774B, com. d, p. 59.) In the section

following the trial court’s capacity analysis in the statement of decision, the court

considered whether there was a reasonable certainty Louise would have received an

inheritance but for the defendants’ interference and whether the defendants’ conduct was

a substantial factor in causing Louise’s harm. The trial court found Frank would have

27

executed the new trust documents but for the defendants’ interference and, “[a]s a result

of defendants’ actions, plaintiff has been deprived of the use and enjoyment of the

decedent’s estate.” Tammy does not challenge the court’s findings in this regard and we

accordingly conclude Louise met her burden of proving causation.

Louise did not have the additional burden of proving mental capacity. Had the

trust documents been executed, Tammy would have had the burden of proving mental

incapacity if she wished to challenge the validity of the trust documents on that ground

because capacity would have been presumed under section 810, subdivision (a). “A

person challenging the validity of a trust instrument on the grounds that the trustor lacked

capacity to execute the document or did so under the undue influence of another carries

the heavy burden of proving such allegations.” (Doolittle v. Exchange Bank, supra, 241

Cal.App.4th at p. 545.) We see no reason nor logic for placing a burden on Louise that

she would not have had to carry if the wrong had not been done. Tammy may not take

advantage of her own wrong. (Civ. Code, § 3517.) Tammy raised mental incapacity as

an affirmative defense; she had the burden of proving the defense.

As to the standard of proof, we agree with Tammy that Doolittle does not stand for

the proposition that mental incapacity must be proven by clear and convincing evidence;

the case states undue influence must be proven by clear and convincing evidence.

(Doolittle v. Exchange Bank, supra, 241 Cal.App.4th at p. 545.) “The default standard of

proof in civil cases is the preponderance of the evidence. [Citation.] Nevertheless, courts

have applied the clear and convincing evidence standard when necessary to protect

important rights.” (Conservatorship of Wendland (2001) 26 Cal.4th 519, 546.) We need

not resolve the parties’ dispute as to the standard of proof because, even if the

preponderance of the evidence standard applies, Tammy did not meet her burden of

proving mental incapacity, as explained post.

28

C

Substantial Evidence Supports The Trial Court’s Capacity Finding

Tammy asserts the undisputed facts are “insufficient as a matter of law to support

a finding of ‘capacity’ under the appropriate Probate Code [section] 812 and Lintz . . .

standard.” This argument is confusing. Sections 811 and 812 deal with the standards for

finding mental incapacity because capacity is presumed. We take Tammy’s argument to

be that the trial court erred in finding she failed to prove Frank was mentally

incapacitated on August 20. The crux of Tammy’s argument is that the trial court failed

to mention “other evidence from witnesses that the trial court found credible,” “[t]he

confluence of [which] reveals that the only possible conclusion in this case is that Frank

could not have reviewed and signed an 80 plus page complex document on the afternoon

of August 20, 2016.” We disagree.

First, Tammy argues the trial court failed to consider Crawford’s testimony that

“Frank was disoriented by 2 to 5 years as to the year” on August 19. Tammy notes,

however, Crawford explained that, in her opinion, the failure to recall the correct year

was not by itself enough to keep Frank from participating in decision-making. Given

Crawford’s explanation, we fail to see the relevance of this testimony.

Second, Tammy argues Crawford’s testimony that Frank was aware of his needs

and requested assistance in response to those needs was contradicted by Crawford’s

testimony on cross-examination, as follows:

“Q: Let’s jump in on that note of August 20th. That’s from Hospice of the

Foothills?

“A: Correct.

“Q: Does that indicate a telephone conversation, in other words, that hospice --

somebody was calling hospice?

“A: Says, ‘T,’ slash, ‘C’, so I assume that’s a telephone conference.

“Q: Yes. Does it indicate who’s calling hospice?

29

“A: I think on the first -- well, the first one says, ‘Telephone call from

[Louise].’

“Q: So wouldn’t it be fair to say that that request for the -- that’s [Louise’s]

versions of who’s requesting the suction machine? In other words --

“A: It does state that ‘[Louise] states the patient is requesting the suction

machine.’

“Q: So there’s [sic] is no confirmation that the patient is making the telephone

call --

“A: Correct.

“Q: But the caretaker for the patient?

“A: Correct. You cannot say on that --

“Q: Right.

“A: -- which way it went, I agree.”

Tammy asserts this testimony demonstrates “there is no confirmation that Frank

Gomez did anything, only that Louise made the call and stated that” he requested

assistance. This does not raise a contradiction in the evidence relied upon by the trial

court. The trial court explained the note relied upon by Crawford was consistent with

Louise’s testimony that Frank had asked for the suction machine and Piffero’s testimony

that Frank was aware and able to request assistance on August 20. The trial court thus

found the content of the note corroborated by testimony it deemed credible.

Third, Tammy believes the trial court failed to credit Crawford’s testimony “about

the effect of the oral morphine sulfate painkiller which Frank had been receiving since

the morning of August 19th, and its effect, and in Dr. Crawford’s opinion, on the ability

of a patient to review and sign complex documents.” In the testimony relied upon,

Crawford was asked: “How long do you think somebody in that situation that’s, you

know, gravely obviously going home on hospice and dying, would be able to sustain, to

stay awake and sustain concentration to review a, let’s say, a 93-page complex

30

document?” Crawford responded: “If I had been given whatever dose of morphine and,

again, how I might respond to a given dose depends on a lot of factors, I would want to

wait at least three to four hours before I had reviewed [documents].”

Tammy argues this testimony combined with the following evidence established

Frank was mentally incapacitated on August 20: (1) the timing of Aanestad’s arrival in

relation to when Frank was last given morphine; (2) Aanestad’s estimate that it would

take a healthy client one to four hours to review and sign trust documents; (3) the timing

of Frank vomiting and losing bowel control; (4) the videos and photos of Frank taken by

Tammy and Christopher on August 20; and (5) the testimony by several witnesses that

Frank was nonresponsive on August 20. Tammy believes, “[p]utting all these pieces

together, the critical window of time for Frank to have been alert enough to review and

sign a complex, 80 plus page trust document . . . [was] between 12:00 and 1:00 p.m.”

Assuming it would have taken Frank four hours to review and sign the documents,

Tammy asserts “it is undisputed on this record that a review and signing would have

physically have to have gone well past the point in time when Frank was throwing up

bile . . . .” Accordingly, in Tammy’s view, “there is no substantial evidence in this record

that would support a finding of fact that Frank had the capacity, even under the erroneous

and lower Probate Code section 6100.5 standard, after the ‘throwing up bile incident’ that

occurred between 12:45 p.m. and 1:00 p.m.”

We first note there was no testimony relating to how or whether the vomiting and

loss of bowel incident affected Frank’s mental capacity. As Tammy acknowledges,

Louise (whom the trial court found credible) testified Frank visited with Farmer that

afternoon and Frank referred to Farmer by the nickname Frank had always used,

“ ‘Chuck E Cheese.’ ” Second, Crawford’s opinion was specifically limited to how long

she would wait if she had been given “whatever dose of morphine.” The testimony is not

specific to the morphine dose Frank received and Crawford did not give an opinion as to

when Frank would have been able to review documents. Other portions of Crawford’s

31

testimony -- which Tammy fails to acknowledge and cite -- directly contradict the

inference Tammy asks us to draw from the quoted portion of Crawford’s testimony.

Crawford affirmatively testified that, as to the morphine Frank received, she did

not expect it to have impacted his decision-making ability. Crawford expected the

medication to help with pain and allow the patient to rest easier. She added: “But I

would anticipate somebody to be able to arouse after being on that dose and have their

normal mentation they had prior to that.” Crawford further said: “I just wanted to say

there’s nothing here in the record or anything that I would ever assume that just because

somebody got that pain medication that they wouldn’t be able to retain capacity in any

area.” Tammy’s attorney responded: “I’m not saying that they wouldn’t have capacity in

any area. I’m saying they wouldn’t have the capacity that we talked about the

hypothetical with the complex trust document.” Crawford clarified: “That’s what I’m

saying. I don’t argue with that. I think it’s very certainly possible somebody could. It

would depend on their response to the medication. Somebody could be more responsive,

more able to attend if their pain was managed correctly.” She continued: “So I can’t tell

from what’s in the record which way that would have gone.”

Third and importantly, Tammy’s argument fails because she does not explain why

the evidence cited by the trial court was insufficient as a matter of law. (See Rayii v.

Gatica (2013) 218 Cal.App.4th 1402, 1408 [“[t]he fact that there was substantial

evidence in the record to support a contrary finding does not compel the conclusion that

there was no substantial evidence to support the judgment”].) Tammy instead asks us to

reweigh the evidence and substitute our judgment for that of the trial court. We decline

to do so. (Conservatorship of O.B. (2020) 9 Cal.5th 989, 1008 [“In assessing how the

evidence reasonably could have been evaluated by the trier of fact, an appellate court

reviewing such a finding is to view the record in the light most favorable to the judgment

below; it must indulge reasonable inferences that the trier of fact might have drawn from

the evidence; it must accept the fact finder’s resolution of conflicting evidence; and it

32

may not insert its own views regarding the credibility of witnesses in place of the

assessments conveyed by the judgment”].)

We find no basis to overturn the trial court’s finding that Frank had the requisite

mental capacity to execute the trust documents on August 20.

VI

The Constructive Trust Is Not Fatally Ambiguous

In the tentative statement of decision, the trial court wrote: “As such, the Court

hereby imposes a constructive trust in favor of plaintiff as to the property of decedent’s

trust estate to be held by plaintiff until her death according to the Frank P. Gomez and

Louise A. Gomez Living Trust drafted by Erik Aanestad at the request of the decedent.

(Ex. 3.)” (Bolding omitted.) Tammy objected to the tentative decision on the ground

that, among other things, the language was ambiguous “as to what is meant by ‘held by

plaintiff until her death.’ Would plaintiff be entitled to income from the Trust for her life,

with the balance going to decedent’s children on her death, as testified to by Ken Meyers,

[citation] or to some principal amount, as well?” Although the trial court modified the

tentative statement of decision, it did not address Tammy’s objection.

The statement of decision provides: “As such, the Court hereby imposes a

constructive trust in favor of plaintiff upon defendants’ share of and rights to the

decedent’s trust estate (including those trust assets already received by them, if any), to

be held by plaintiff until her death, according to the Frank P. Gomez and Louise A.

Gomez Living Trust drafted by Erik Aanestad at the request of the decedent. (Ex. 3.)”

(Bolding omitted.) Tammy argues the constructive trust is fatally ambiguous because the

trial court failed to address the question posed in her objection to the tentative decision.

Louise does not address the argument.

“An ambiguity is said to exist in an instrument when the written language is fairly

susceptible of two or more constructions.” (Estate of White (1970) 9 Cal.App.3d 194,

200.) The statement of decision is clear that Louise shall have a life estate according to

33

the terms of the living trust attached thereto as an exhibit. Tammy’s effort to construct an

ambiguity is unconvincing. Should a dispute arise in the future regarding Louise’s use of

the trust estate, the trial court may address it at that time.

Outcome: The judgment is affirmed. Louise shall recover her costs on appeal. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.278(a)(1)-(2).)

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments:

Find a Lawyer

Find a Case